The 21st century has already witnessed the tragic loss of several reptile species, marking a concerning trend in our planet’s biodiversity decline. While reptiles have survived for over 300 million years through numerous global catastrophes, they now face unprecedented threats from human activities.

Climate change, habitat destruction, invasive species, and direct exploitation have accelerated extinction rates to alarming levels.

This article examines the reptile species we have already lost since 2000, highlighting the urgent need for conservation efforts and the factors driving these extinctions.

Each loss represents not just the disappearance of a unique evolutionary lineage but also disruption to ecosystems and the diminishment of our planet’s natural heritage.

The Pinta Island Tortoise: An Iconic Loss

Perhaps the most famous reptile extinction of the 21st century is that of the Pinta Island Tortoise (Chelonoidis abingdonii), with the death of “Lonesome George” in 2012 marking the end of his species.

As the last known individual of his kind, George became a conservation icon and lived at the Charles Darwin Research Station in the Galapagos for decades while scientists unsuccessfully attempted to find him a mate.

His species had been decimated by hunting in the 19th century when sailors and pirates captured tortoises for food, as they could survive for months in ship holds without food or water.

The Pinta Island Tortoise played a crucial ecological role as a herbivore, modifying vegetation and dispersing seeds throughout its native island ecosystem, and its loss represents both an evolutionary tragedy and an ecosystem disruption.

The Christmas Island Forest Skink’s Quiet Disappearance

The Christmas Island Forest Skink (Emoia nativitatis) was declared extinct in 2014, with the death of the last known individual in captivity marking the end of a species that was once common across its island habitat.

This small lizard, endemic to Christmas Island in the Indian Ocean, experienced a catastrophic population collapse in the early 2000s that puzzled scientists.

Researchers believe that the introduction of invasive species, particularly the yellow crazy ant and the wolf snake, devastated the skink population through predation and competition.

The skink’s decline was so rapid that conservation efforts began too late, with attempts to establish a captive breeding program ultimately failing.

This extinction demonstrates how quickly island endemics can disappear once ecological balance is disrupted, often before adequate studies or conservation plans can be implemented.

The Tragic Case of the Rabbs’ Fringe-Limbed Treefrog

While technically an amphibian rather than a reptile, the Rabbs’ Fringe-Limbed Treefrog (Ecnomiohyla rabborum) represents one of the most poignant extinction stories of recent years and illustrates similar threats facing reptiles.

Discovered in Panama only in 2005, the last known individual, nicknamed “Toughie,” died in captivity at the Atlanta Botanical Garden in 2016.

This remarkable species had evolved unique adaptations, including the ability to glide between trees using its large, webbed feet and males that would allow their young to feed on their skin.

The primary cause of its extinction was the devastating chytrid fungus (Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis), which has decimated amphibian populations worldwide.

The frog’s rapid discovery-to-extinction timeline highlights how quickly species can disappear in the modern era, sometimes before scientists can fully understand their biology or ecological significance.

Christmas Island Whiptail-Skink: Gone Too Soon

The Christmas Island Whiptail-Skink (Emoia atrocostata) was officially declared extinct in the wild by 2010, with only a handful of individuals surviving in captivity for a few more years.

Endemic to Christmas Island, this skink species suffered from the same invasive predators that claimed the Forest Skink, particularly the voracious wolf snake (Lycodon capucinus), which was accidentally introduced to the island in the 1980s.

Scientists observed a dramatic population collapse in the early 2000s, with surveys finding fewer individuals each year until none could be located.

The extinction of this species represents another loss in the concerning pattern of reptile extinctions on Christmas Island, which has become a hotspot for biodiversity loss due to its isolation and vulnerability to invasive species.

The island has now lost several endemic reptile species in just two decades, creating a ripple effect through the island’s unique ecosystem.

The Lost Geckos of New Caledonia

New Caledonia, a biodiversity hotspot in the South Pacific, has lost several gecko species in recent decades, with some confirmed extinctions occurring in the 21st century.

The New Caledonian Giant Gecko (Rhacodactylus leachianus) has experienced significant population declines, with some subspecies potentially already extinct. These remarkable geckos evolved in isolation and developed unique characteristics, including vocalizations unusual among reptiles.

Their decline has been attributed primarily to habitat destruction through mining operations, as New Caledonia contains approximately 25% of the world’s nickel reserves, leading to extensive habitat clearing.

Additionally, introduced predators such as rats and cats have devastated gecko populations unprepared for mammalian predation.

The loss of these geckos represents a significant blow to both the biodiversity of New Caledonia and to our understanding of reptile evolution in isolated island systems.

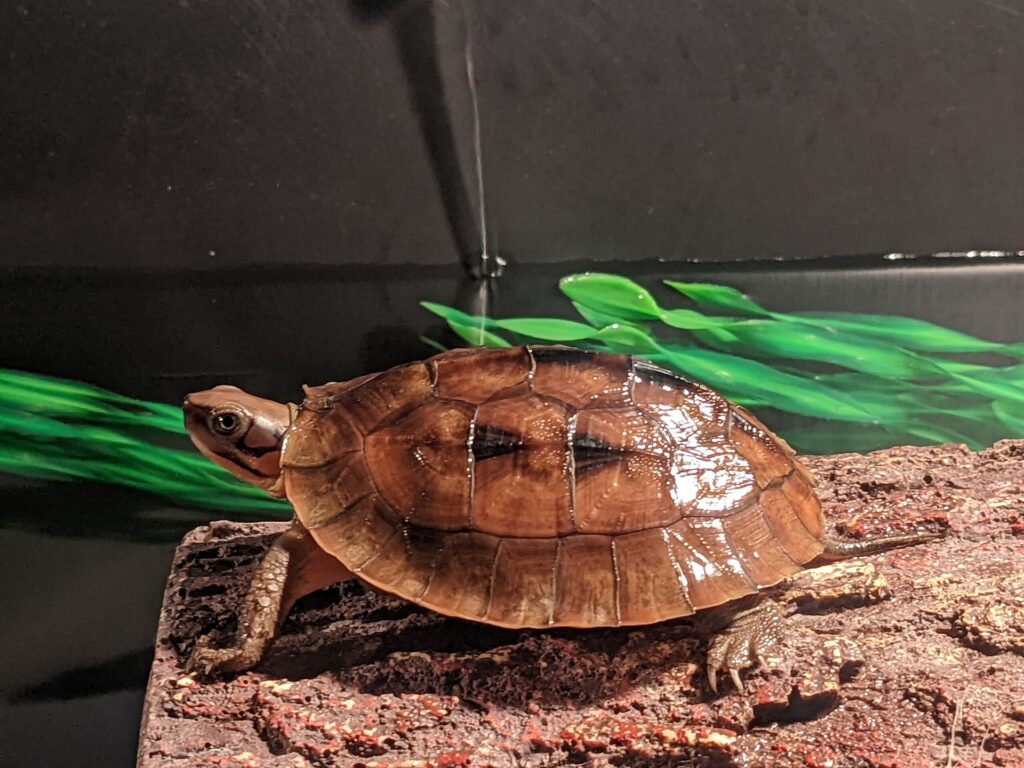

Vietnam’s Box Turtles: Eaten to Extinction

The Vietnamese Box Turtle (Cuora vietnamensis) is considered functionally extinct in the wild, with the last verified wild sightings occurring in the early 2000s. While a few individuals may still exist in captivity, the species has been effectively lost from its natural habitat due to unsustainable harvesting for the Asian food and medicine markets.

These turtles were highly prized in traditional Chinese medicine, with their shells and body parts believed to have healing properties, leading to intensive collection that rapidly depleted wild populations.

Habitat destruction through agricultural expansion and urbanization further compressed their remaining range, making it easier for poachers to locate and capture the last individuals.

The Vietnamese Box Turtle’s disappearance highlights the devastating impact of wildlife trafficking and traditional medicine markets on reptile species, particularly in Southeast Asia, where many tortoise and turtle species face similar threats.

Caribbean Reptile Extinctions: The Silent Crisis

The Caribbean islands have experienced multiple reptile extinctions in the 21st century, creating an often-overlooked biodiversity crisis. Several endemic lizard species in the genus Leiocephalus have disappeared from islands including Jamaica, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic.

The Round Island Burrowing Boa (Bolyeria multocarinata) of Mauritius was declared extinct after extensive surveys failed to locate any specimens since 1975, with the official extinction declaration coming in the early 2000s.

Caribbean reptile extinctions have been driven by a combination of habitat conversion for tourism development, introduced predators like mongooses and feral cats, and climate change effects, including stronger hurricanes that can devastate small island populations.

The isolated evolution of these island reptiles made them particularly vulnerable to new threats, as they developed in environments with few natural predators and limited competition, resulting in specialized adaptations that became disadvantages when faced with invasive species.

Australia’s Declining Reptile Fauna

Australia, home to approximately 10% of the world’s reptile species, has already experienced several reptile extinctions in the 21st century. The Bramble Cay melomys, while technically a mammal, shared habitat and extinction drivers with several vulnerable reptile species, highlighting the vulnerability of island fauna.

Australia’s Christmas Island has been particularly hard-hit, losing several endemic reptile species, including the Christmas Island Blind Snake (Ramphotyphlops exocoeti), which was declared extinct after extensive surveys failed to locate any specimens since 2000.

These extinctions have been driven by introduced predators, particularly feral cats, which kill an estimated 466 million reptiles annually in Australia, along with habitat modification through agriculture, mining, and urbanization.

Climate change poses an additional threat to Australian reptiles, with rising temperatures particularly concerning for species with temperature-dependent sex determination, where warmer incubation temperatures can skew populations toward predominantly one sex.

Madagascar’s Vanishing Reptile Diversity

Madagascar, renowned for its exceptional reptile diversity and endemism, has likely already lost several reptile species in the 21st century, though documentation remains challenging in this biodiversity hotspot.

Several chameleon species, including members of the genus Calumma, have not been observed for decades despite targeted surveys, leading scientists to fear they have already been lost.

Madagascar’s reptile extinctions are primarily driven by unprecedented rates of deforestation, with the island losing over 40% of its forest cover since the 1950s, primarily for agriculture, charcoal production, and mining.

Climate change has compounded these threats, with changing rainfall patterns affecting the highly specialized microhabitats many Malagasy reptiles require.

The potential extinction of these species represents not only a loss of biodiversity but also the disappearance of evolutionary adaptations found nowhere else on Earth, such as the remarkable camouflage strategies of Madagascar’s chameleons or the specialized habitat requirements of its plated lizards.

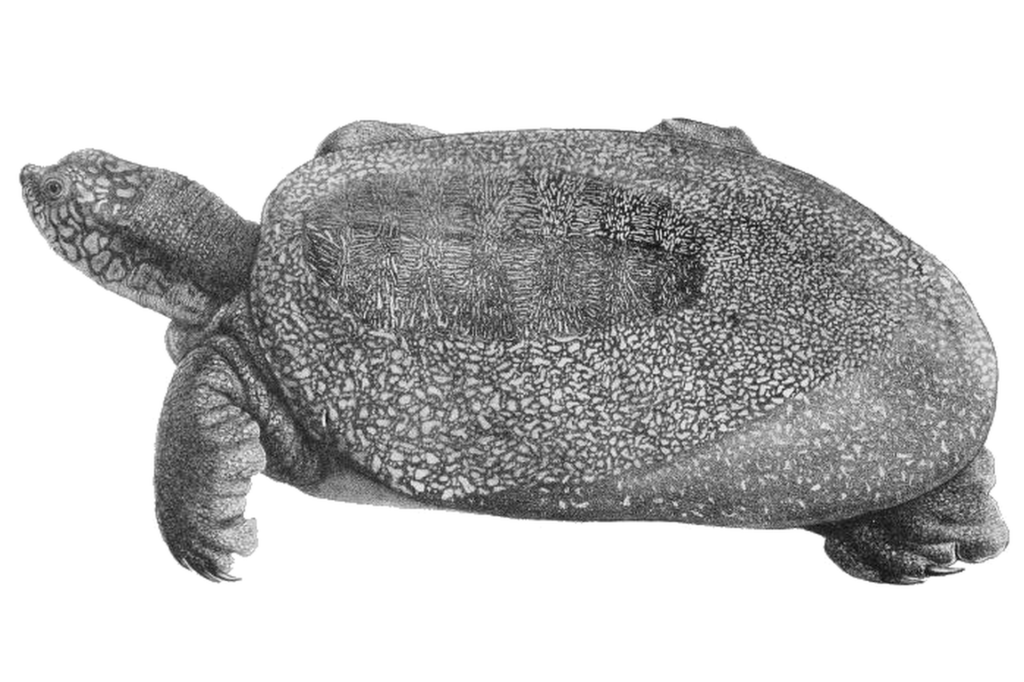

The Yangtze Giant Softshell Turtle: On the Brink

While not technically extinct yet, the Yangtze Giant Softshell Turtle (Rafetus swinhoei) represents one of the most critical reptile conservation crises of the 21st century, with only three known individuals remaining alive as of 2023.

This species, which can reach over 100kg in weight and live more than a century, was once common in the Yangtze River basin and Vietnamese lakes but has been devastated by habitat loss, pollution, and hunting.

The death of the last known female at Suzhou Zoo in China in 2019 represented a devastating blow to conservation efforts, as attempts at artificial insemination had been unsuccessful.

The remaining individuals include one in captivity in China and two in Vietnam, with no known females, making the functional extinction of this species almost certain without a miraculous discovery of additional specimens.

The impending loss of this evolutionary distinct species, which diverged from other turtles over 40 million years ago, represents not just the disappearance of a species but of an entire genetic lineage.

The Role of Climate Change in Modern Reptile Extinctions

Climate change has emerged as a significant driver of reptile extinctions in the 21st century, with effects that are both direct and interacting with other threats.

Rising temperatures particularly impact reptiles with temperature-dependent sex determination, as seen in many turtle and crocodilian species, where warmer incubation temperatures can produce offspring of predominantly one sex, potentially leading to reproductive collapse.

Changing precipitation patterns affect habitat suitability and prey availability, while increasing frequency and intensity of extreme weather events can devastate small, isolated populations. Sea level rise threatens coastal and island reptile species, with species like the Bramble Cay snake losing habitat to inundation.

Perhaps most concerning is how climate change interacts with and amplifies other threats, creating “extinction synergies” that accelerate biodiversity loss beyond what any single threat might cause in isolation, as seen in the case of several Caribbean and Pacific island reptile extinctions.

Conservation Lessons from Recent Reptile Extinctions

The reptile extinctions of the 21st century offer valuable, if sobering, lessons for conservation biology. One key insight is the heightened vulnerability of island endemics, which have evolved in isolation and often lack adaptations to invasive predators or competitors, as demonstrated by the Christmas Island extinctions.

The rapid timeline from discovery to extinction seen in several cases highlights the urgent need for proactive rather than reactive conservation approaches, particularly in biodiversity hotspots facing development pressures.

The failures of last-minute captive breeding programs for several species underscore the importance of establishing insurance populations before wild numbers become critically low.

Additionally, these extinctions demonstrate the need for integrated conservation approaches that address multiple threats simultaneously, as most extinctions resulted from a combination of pressures rather than a single cause.

Perhaps most importantly, these losses emphasize the irreversible nature of extinction – once a species is gone, its unique evolutionary history and ecological role are permanently lost to the planet.

The Future of Reptile Conservation in the Anthropocene

As we move further into the 21st century, the fate of many reptile species hangs in the balance, with conservation efforts racing against accelerating threats.

Technological innovations offer some hope, including environmental DNA (eDNA) sampling that can detect the presence of critically endangered species from water or soil samples, potentially revealing populations previously thought extinct.

Advanced genetic techniques may help address inbreeding depression in small populations and potentially even resurrect extinct species through de-extinction technologies, though such approaches remain controversial.

More conventional but essential approaches include habitat protection and restoration, biosecurity measures to prevent invasive species introductions, and sustainable development planning that incorporates biodiversity conservation.

Public engagement and education represent another vital component, as increased awareness of the ecological importance of reptiles can counteract negative perceptions and build support for conservation initiatives.

Ultimately, preventing further reptile extinctions will require unprecedented cooperation across governments, conservation organizations, communities, and industries, recognizing that preserving biodiversity is fundamental to human wellbeing and planetary health.

Conclusion

The 21st century has already witnessed the permanent loss of several remarkable reptile species, each extinction representing not just the end of a unique evolutionary lineage but also a warning about the accelerating state of our planet’s biodiversity crisis.

From the iconic Lonesome George to the lesser-known skinks of Christmas Island, these extinctions share common drivers: habitat destruction, invasive species, overexploitation, and the overarching threat of climate change.

Yet within these tragedies lie important lessons and, perhaps, motivation for more effective conservation. The remaining reptile species facing extinction could still be saved through coordinated action, political will, and innovative approaches.

As we reflect on what has already been lost in just the first decades of this century, we must recognize that preventing further reptile extinctions is not merely about preserving biodiversity for its own sake but about maintaining the complex ecological relationships that ultimately support all life on Earth, including our own.