In the shadowy depths of rivers, lurking beneath murky swamps, and patrolling coastlines across tropical regions, crocodiles reign as ancient predators virtually unchanged for millions of years. These formidable reptiles have earned their reputation as some of the planet’s most efficient hunters and dangerous creatures.

With powerful jaws exerting tremendous bite force, armored bodies, and surprising bursts of speed, certain crocodile species have become particularly notorious for their aggression toward humans and their impressive physical capabilities.

This article explores the world’s most dangerous crocodilian species, examining what makes them especially hazardous, their hunting behaviors, geographical distribution, and the complex relationship between humans and these apex predators.

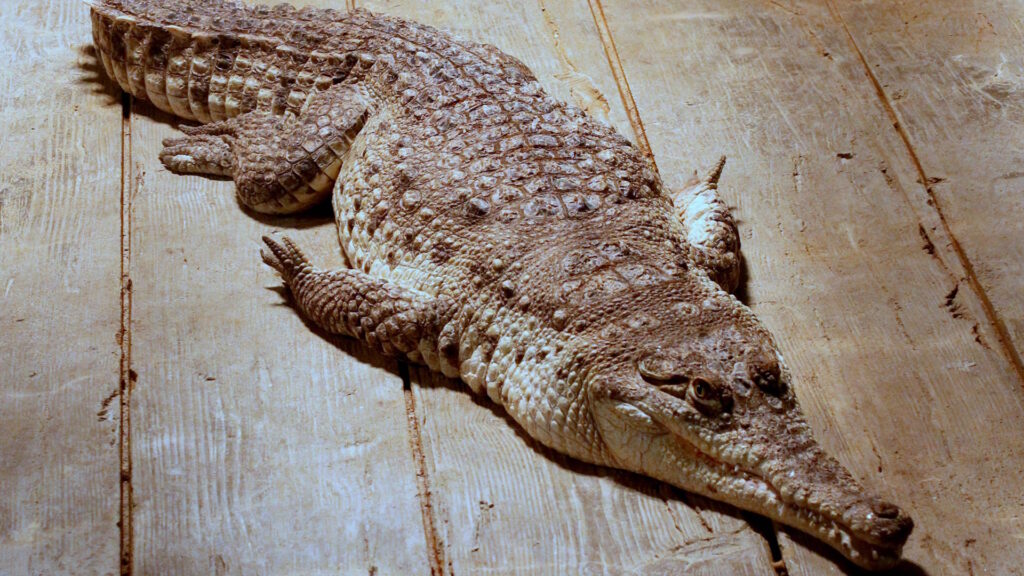

Saltwater Crocodile: The Undisputed King

The saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus), also known as the estuarine crocodile, stands as the undisputed heavyweight champion in the crocodilian world and arguably the most dangerous to humans. Growing to lengths exceeding 20 feet and weighing up to 2,200 pounds, these massive reptiles possess the strongest bite force of any animal on Earth, measuring an astonishing 3,700 pounds per square inch.

Their distribution spans across northern Australia, eastern India, Southeast Asia, and the islands of the Pacific, adapting seamlessly to both freshwater environments and saltwater coastal areas. Saltwater crocodiles are particularly dangerous due to their territorial aggression, immense size, and their tendency to view humans as prey, unlike many other predators that typically avoid human confrontation.

Nile Crocodile: Africa’s Notorious Predator

The Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus) has earned its fearsome reputation as one of Africa’s most prolific predators and is responsible for hundreds of human fatalities annually. Distributed widely across sub-Saharan Africa, these crocodiles can grow up to 16 feet long and weigh as much as 1,650 pounds, making them the second-largest crocodilian species.

What makes Nile crocodiles particularly dangerous is their proximity to dense human populations along Africa’s major river systems, creating frequent human-crocodile encounters. These reptiles are capable of remarkable stealth, often attacking from the water’s edge with explosive speed, dragging unsuspecting victims into the water before performing their signature “death roll” – a violent spinning maneuver used to tear apart prey too large to swallow whole.

Research suggests that Nile crocodiles are responsible for more human deaths annually than any other crocodilian species.

Black Caiman: The Amazon’s Apex Predator

Lurking in the waterways of the Amazon Basin, the black caiman (Melanosuchus niger) has established itself as the largest predator in this biodiverse ecosystem. Growing up to 14 feet in length, though historical accounts suggest they once regularly reached 20 feet before hunting reduced their average size, these massive reptiles dominate their habitat with few natural predators.

Black caimans possess distinctive dark coloration that provides excellent camouflage in the tannin-rich blackwater rivers and lagoons they inhabit. While not studied as extensively as other large crocodilians, attacks on humans do occur, particularly in remote areas where people rely on rivers for transportation, fishing, and daily activities.

Their powerful jaws and aggressive territorial behavior make them particularly dangerous during the breeding season when they fiercely defend nesting sites.

Mugger Crocodile: The Subcontinental Stalker

The mugger crocodile (Crocodylus palustris), also known as the marsh crocodile, represents one of the most dangerous crocodilians across the Indian subcontinent, inhabiting Pakistan, India, Sri Lanka, and parts of Iran. Growing to lengths of 13-15 feet, these medium-sized crocodiles have adapted to a wide range of freshwater habitats, including rivers, lakes, and even artificial reservoirs.

What makes mugger crocodiles particularly concerning is their remarkable adaptability to human-altered environments and their willingness to inhabit areas close to human settlements. Unlike some crocodilian species that flee from human presence, muggers have demonstrated remarkable boldness, sometimes even hunting on land and traveling considerable distances between water bodies.

In areas of India and Sri Lanka, they are responsible for numerous attacks annually, particularly during monsoon seasons when flooding increases their range and brings them into closer contact with people.

American Crocodile: The Caribbean Hunter

The American crocodile (Crocodylus acutus) inhabits coastal areas from southern Florida through the Caribbean and Central America to northern South America, representing one of the most widely distributed crocodilian species in the Americas. Growing to lengths of 13-16 feet, these powerful reptiles are primarily found in brackish coastal environments, mangrove swamps, and river mouths, though they can tolerate freshwater habitats as well.

While generally considered less aggressive toward humans than their saltwater or Nile counterparts, American crocodiles still possess all the physical attributes that make crocodilians dangerous – powerful jaws, incredible stealth, and surprising bursts of speed. Attacks on humans are relatively rare but do occur, particularly in areas where habitat encroachment has increased human-crocodile interactions.

Their conservation status has improved in recent decades in the United States, leading to more frequent sightings in developed areas of South Florida.

Orinoco Crocodile: The Endangered Giant

The Orinoco crocodile (Crocodylus intermedius) stands as one of the most critically endangered crocodilian species, yet remains among the most formidable and potentially dangerous. Native to the Orinoco River basin in Colombia and Venezuela, these massive reptiles can reach lengths of 16-17 feet, with historical reports suggesting specimens over 20 feet existed before intensive hunting severely reduced their populations.

While human attacks are now rare due to their depleted numbers, Orinoco crocodiles possess a naturally aggressive temperament and territorial behavior that makes encounters potentially deadly. Their slender snouts and powerful bodies are perfectly adapted for capturing prey in the fast-flowing sections of the Orinoco River system.

Conservation efforts are now focused on protecting remaining populations, though habitat loss and continued poaching present ongoing challenges to their recovery.

Philippine Crocodile: Small but Deadly

The Philippine crocodile (Crocodylus mindorensis) proves that dangerous crocodilians come in various sizes, as this critically endangered species rarely exceeds 10 feet in length yet remains a significant potential threat to humans. Endemic to the Philippines, these freshwater crocodiles have suffered dramatic population declines due to habitat destruction, leaving only a few hundred individuals in the wild.

While smaller than many crocodilian species, Philippine crocodiles compensate with a particularly aggressive temperament when threatened or when defending territory. Their relatively compact size allows them to inhabit smaller water bodies close to human settlements, increasing the potential for dangerous interactions.

Conservation efforts have increased awareness about these crocodiles, though conflict with local communities remains a challenge as humans and crocodiles compete for increasingly limited freshwater resources.

Cuban Crocodile: The Agile Attacker

The Cuban crocodile (Crocodylus rhombifer) may have a limited distribution, confined primarily to the Zapata Swamp of Cuba, but it compensates with exceptional physical capabilities that make it one of the world’s most dangerous crocodilians. Measuring 7-10 feet in length, these medium-sized crocodiles possess remarkably powerful hind legs that enable them to leap completely out of the water and even gallop on land at speeds reaching 11 mph.

This unusual mobility, combined with highly aggressive territorial behavior, creates a formidable predator despite its relatively small size. Cuban crocodiles have evolved as specialized hunters of larger prey, developing more complex hunting techniques than many other crocodilian species.

Their intelligence is considered among the highest in the crocodilian order, with demonstrated problem-solving abilities and coordinated hunting behaviors rarely seen in reptiles.

Gharial: The Fish-Eating Specialist

The gharial (Gavialis gangeticus) presents a fascinating contradiction in the crocodilian world – while possessing an intimidating appearance with its elongated, needle-like snout filled with 110 interlocking teeth, it rarely poses a threat to humans. Native to the northern Indian subcontinent, these highly specialized fish-eaters have suffered catastrophic population declines, now being critically endangered.

Growing up to 20 feet in length, gharials are physically impressive but have specialized jaws adapted for catching slippery fish rather than mammalian prey. The narrow snout lacks the crushing strength of other crocodilians, making it ineffective for attacking larger animals.

However, males develop a distinctive bulbous growth at the tip of their snout called a “ghara” (meaning “pot” in Hindi), which can be intimidating and has been known to inflict injuries during territorial disputes or when the animals feel threatened by human encroachment.

False Gharial: The Secretive Swamp Dweller

The false gharial (Tomistoma schlegelii), also known as the Malayan gharial, represents one of the most mysterious and potentially dangerous crocodilians inhabiting the peat swamps and freshwater systems of Malaysia, Indonesia, and parts of Thailand. Growing to impressive lengths of 13-16 feet, these reptiles possess distinctive elongated snouts similar to true gharials but maintain the broader jaw structure and stronger bite force characteristic of crocodiles.

While historically considered primarily fish-eaters like their Indian gharial relatives, recent research suggests false gharials regularly prey on larger mammals, birds, and reptiles, indicating more generalist predatory behavior.

Human attacks are poorly documented due to their remote habitat and declining numbers, but their physical capabilities certainly place them among potentially dangerous crocodilians. Their secretive nature and the inaccessibility of their swamp habitats have hampered detailed scientific study, leaving many aspects of their behavior and ecology poorly understood.

Siamese Crocodile: The Endangered Survivor

The Siamese crocodile (Crocodylus siamensis) once dominated freshwater habitats throughout Southeast Asia but has now been reduced to critically endangered status with perhaps fewer than 1,000 wild individuals remaining. Growing to moderate lengths of 10-13 feet, these crocodiles inhabit slow-moving rivers, lakes, and marshes across Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam.

While considered less aggressive toward humans than some other species, Siamese crocodiles remain potentially dangerous predators, particularly during breeding season when defending territories and nests. Their decline has been primarily driven by habitat loss, hunting for their skins, and collection of live specimens for crocodile farms, where they are often hybridized with saltwater crocodiles to produce commercially valuable offspring.

In areas where Siamese crocodiles persist, they maintain their ecological role as apex predators, though human encounters have become increasingly rare due to their depleted numbers.

Human-Crocodile Conflict: Understanding the Danger

The danger posed by crocodilians to humans must be understood within the context of expanding human populations and decreasing natural habitat. Most attacks occur during routine activities like fishing, collecting water, bathing, or crossing waterways in areas where crocodiles live.

The World Health Organization estimates that crocodilians kill approximately 1,000 people annually, with the highest fatality rates occurring in Southeast Asia and Africa. Interestingly, crocodilian attacks follow distinct patterns depending on species and geography – Nile crocodiles often attack during daytime activities along riverbanks, while saltwater crocodiles more frequently target people in boats or swimming.

Understanding attack patterns has helped some communities develop mitigation strategies, including physical barriers around water access points, educational programs, and crocodile monitoring efforts. However, as human populations continue expanding into crocodile habitat, the frequency of dangerous encounters will likely increase without comprehensive management approaches.

Conservation vs. Safety: A Delicate Balance

The paradox of crocodilian conservation presents one of wildlife management’s most challenging dilemmas – how to protect these ecologically important apex predators while ensuring human safety. In Australia’s Northern Territory, a sustainable management approach has successfully balanced saltwater crocodile conservation with public safety, implementing strict zoning, education programs, and targeted removal of problem animals.

Conversely, in many developing nations where dangerous crocodile species exist, limited resources and competing priorities often result in reactionary management, with crocodiles killed after attacks rather than preventative measures being implemented. The most successful models recognize that crocodilians serve vital ecological functions, controlling prey populations and maintaining wetland health, while acknowledging the legitimate safety concerns of local communities.

Effective strategies typically combine habitat protection, controlled sustainable use where appropriate, comprehensive education programs, and protocols for addressing animals that pose immediate threats to human safety.

Conclusion

The world’s most dangerous crocodiles represent the perfect evolutionary predators, having survived virtually unchanged since the age of dinosaurs. Their remarkable physical adaptations, territorial behavior, and predatory instincts make certain species particularly hazardous to humans who share their environments.

From the massive saltwater crocodile of Australia and Southeast Asia to Africa’s notorious Nile crocodile, these reptiles deserve both our respect and caution. As human populations continue expanding into traditional crocodile territories, understanding these formidable creatures becomes increasingly important for conservation and public safety alike.

With proper education, habitat management, and coexistence strategies, it is possible to minimize dangerous encounters while ensuring these ancient predators continue fulfilling their critical ecological roles for generations to come.