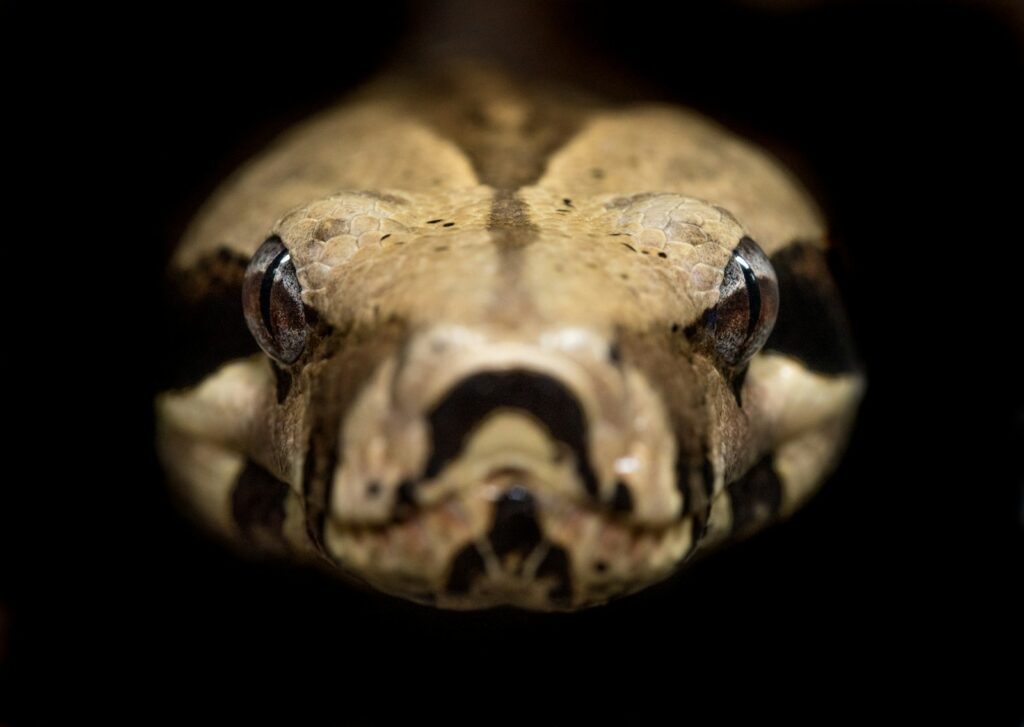

Snakes have fascinated and terrified humans throughout history. While most species are harmless to humans, certain serpents possess venom so potent that a single bite can lead to death within hours or even minutes. This ranking explores the world’s most lethal snakes based on a combination of venom toxicity, aggressiveness, distribution near human populations, and recorded fatalities. Understanding these creatures isn’t just about feeding our fear—it’s about respecting wildlife and knowing how to stay safe in snake territories. Let’s slither into the dangerous world of the planet’s deadliest serpents, where beauty often conceals deadly biological weapons.

What Makes a Snake Deadly?

When evaluating which snakes deserve the title of “deadliest,” several factors must be considered beyond simple venom potency. The lethality of a snake depends on the toxicity of its venom (measured by LD50 values—the amount needed to kill 50% of test subjects), the average venom yield per bite, the efficiency of its delivery system, and its proximity to human populations. Additionally, behavioral factors like aggressiveness, defensive tendencies, and likelihood to strike play crucial roles in determining real-world danger. Some highly venomous snakes rarely bite humans, while others with “weaker” venom cause more deaths due to their habitat overlap with dense human settlements or lack of available antivenom. This complex interplay of factors creates a more nuanced picture than laboratory toxicity alone could provide.

Inland Taipan: The Most Venomous Snake on Earth

The Inland Taipan (Oxyuranus microlepidotus), also known as the “fierce snake,” tops the list with venom approximately 200-400 times more toxic than a common cobra’s. A single bite from this Australian native delivers enough venom to kill up to 100 adult humans, with its neurotoxic, hemotoxic, and myotoxic components attacking the nervous system, blood, and muscles simultaneously. Despite possessing this incredibly potent cocktail, the Inland Taipan rarely encounters humans due to its remote habitat in the arid regions of central east Australia. This snake is naturally shy and prefers to avoid confrontation, which explains why there are no recorded deaths from this species in recent history. Its reputation as the “most venomous” rather than “deadliest” highlights the important distinction between venom potency and actual human fatalities.

Eastern Brown Snake: Australia’s Lethal Defender.

The Eastern Brown Snake (Pseudonaja textilis) ranks as the second most venomous land snake and causes more deaths in Australia than any other snake species. This slender, fast-moving predator possesses extremely potent neurotoxic venom that rapidly causes paralysis and prevents blood clotting, with victims potentially collapsing within minutes. Unlike the Inland Taipan, Eastern Browns frequently encounter humans as they thrive in populated areas and agricultural regions across eastern Australia. Their defensive nature leads them to stand their ground when threatened, raising their body in an S-shaped striking position. What makes them particularly dangerous is their tendency to strike repeatedly when agitated, combined with the fact that their bites are often painless and may go unnoticed until serious symptoms develop—by which time treatment becomes much more challenging.

Coastal Taipan: The Lightning-Fast Killer

The Coastal Taipan (Oxyuranus scutellatus) combines extreme venom potency with alarming speed and aggression when cornered. This Australian serpent delivers one of the most toxic venoms in the world, containing a complex mixture of neurotoxins, hemotoxins, myotoxins, and nephrotoxins that attack multiple body systems simultaneously. When a Coastal Taipan strikes, it often bites multiple times in a single attack, injecting massive amounts of venom with surgical precision. The venom acts rapidly to prevent blood clotting, destroy muscle tissue, and cause paralysis, with untreated bites having a mortality rate approaching 100% before antivenom became available. Despite their lethal potential, these snakes typically attempt to flee from human encounters, only becoming aggressive when cornered or threatened—a characteristic that somewhat mitigates their dangerousness despite their deadly venom.

Russell’s Viper: Asia’s Silent Assassin

Russell’s Viper (Daboia russelii) is responsible for more human deaths than almost any other snake worldwide, particularly across its range in India, Southeast Asia, and parts of China. This heavy-bodied snake delivers a massive venom yield containing hemotoxins that cause catastrophic disruption to blood clotting mechanisms, leading to internal bleeding, tissue necrosis, and potential organ failure. What makes Russell’s Vipers especially dangerous is their widespread distribution in densely populated agricultural areas, combined with their habit of freezing when approached rather than fleeing, leading to accidental encounters with farmers and rural workers. The venom’s effects develop over hours, initially causing intense pain and swelling, followed by more serious systemic effects that can include kidney failure and pituitary gland hemorrhage—a unique and particularly devastating long-term complication seen in survivors.

Saw-Scaled Viper: Small Size, Deadly Reputation

The Saw-Scaled Viper (Echis carinatus) family demonstrates that size doesn’t always correlate with danger when it comes to venomous snakes. Though rarely exceeding 60-70 centimeters (2-2.3 feet), these relatively small vipers cause more human fatalities than any other snake species globally. Their hemotoxic venom disrupts blood clotting mechanisms, causing internal hemorrhaging and tissue death, with mortality rates exceeding 20% in untreated cases. What makes them particularly dangerous is their combination of aggressive defensive behavior, distinctive side-winding locomotion, and a wide distribution across some of the world’s most densely populated regions including India, the Middle East, and Central Africa. Their characteristic threat display involves rubbing sections of their body together to produce a distinctive rasping sound—a warning that should never be ignored, as they’re known to strike with minimal provocation and lightning-fast reflexes.

Black Mamba: Africa’s Lightning-Fast Terror

The Black Mamba (Dendroaspis polylepis) has earned its fearsome reputation as Africa’s most dangerous snake through a combination of speed, aggression, and exceptionally potent neurotoxic venom. Capable of reaching speeds up to 12.5 mph (20 km/h), this snake can outpace a running human over short distances, making escape difficult when confronted. A Black Mamba’s venom attacks the nervous system with devastating efficiency, causing respiratory paralysis that can lead to death within 20 minutes in the most severe cases, though 2-3 hours is more typical without antivenom. Unlike many venomous snakes that prefer to retreat, Black Mambas may actively defend their territory, delivering multiple strikes in rapid succession when threatened. Their length (averaging 8-10 feet but sometimes reaching 14 feet) allows them to strike at head height for humans, making encounters particularly dangerous in the grasslands and rocky hills of sub-Saharan Africa where they typically dwell.

Philippine Cobra: The Spitting Death

The Philippine Cobra (Naja philippinensis) represents one of the deadliest members of the cobra family due to its highly neurotoxic venom and unique defensive capabilities. What sets this species apart from many other venomous snakes is its ability to “spit” venom with remarkable accuracy at a target’s eyes from distances up to three meters, causing intense pain and potential blindness if not immediately washed out. When this cobra delivers a bite, its potent neurotoxin attacks the respiratory system rapidly, potentially causing death from respiratory failure within 30 minutes—making it one of the fastest-acting snake venoms known. Endemic to the northern regions of the Philippines, this snake often encounters humans in agricultural areas, contributing to its high fatality count in the region. Their relatively calm disposition compared to other cobras creates dangerous situations where humans might not recognize the imminent threat until it’s too late.

King Cobra: The Royal Serpent

The King Cobra (Ophiophagus hannah) commands respect as the world’s longest venomous snake, capable of reaching lengths over 18 feet and delivering enough neurotoxic venom in a single bite to kill 20 adult humans or even an elephant. Unlike many other deadly snakes, the King Cobra demonstrates remarkable intelligence and awareness, with the ability to recognize individual humans and remember those who have threatened them previously. Their venom specifically targets the central nervous system, gradually shutting down nerve signals to the muscles responsible for breathing, causing respiratory failure within hours if left untreated. When threatened, they display one of the animal kingdom’s most impressive defensive postures, raising the front third of their body off the ground, flaring their distinctive hood, and emitting a bone-chilling hiss that sounds remarkably like a growling dog. Despite their fearsome capabilities, King Cobras generally avoid human contact and primarily feed on other snakes—even cannibalistic consumption of their own species—earning them their scientific name which translates to “snake eater.”

Tiger Snake: Australia’s Striped Killer

The Tiger Snake (Notechis scutatus) of southern Australia combines highly potent neurotoxic venom with a defensive temperament, making it one of the continent’s deadliest serpents. Named for the distinctive yellow and black bands that adorn some members of the species (though coloration varies significantly), Tiger Snakes possess venom comparable to that of the feared Coastal Taipan. When threatened, these snakes flatten their necks and raise their heads in a cobra-like display before striking with remarkable speed and precision. Their venom contains a powerful cocktail of neurotoxins, coagulants, and myotoxins that can cause paralysis, muscle damage, and uncontrollable bleeding, with death by respiratory failure possible within 30 minutes in severe untreated cases. Tiger Snakes frequently inhabit wetlands and waterways near populated areas, including some Australian city parks, increasing the likelihood of human encounters and contributing to their high historical fatality rate before widespread antivenom availability.

Blue Krait: The Night Assassin

The Blue Krait (Bungarus candidus) represents one of Southeast Asia’s most lethal serpents, with venom estimated to be 16 times more potent than that of a cobra. This nocturnal hunter is particularly dangerous because it often enters human dwellings at night in search of prey, leading to bites that occur while victims sleep. The initial bite may be virtually painless, causing victims to remain unaware they’ve been envenomated until serious symptoms develop hours later. Blue Krait venom contains powerful neurotoxins that cause progressive paralysis, eventually affecting the diaphragm and leading to respiratory failure. What makes kraits especially treacherous is their docile nature during daylight hours, when they rarely bite even when handled—creating a false sense of security that contrasts sharply with their aggressive nighttime behavior. Medical statistics show that even with antivenom treatment, the mortality rate from Blue Krait bites remains alarmingly high at approximately 50%, making it one of the few snakes for which antivenom doesn’t dramatically improve survival odds.

Death Adder: The Ambush Specialist

The Death Adder (Acanthophis species) earns its ominous name through a combination of deadly venom and unique hunting strategy that makes it particularly dangerous to unwary humans. Unlike most venomous snakes that actively pursue prey or flee from larger threats, Death Adders are ambush predators that bury themselves in leaf litter or sand, remaining perfectly still while wiggling just the tip of their tail to mimic a worm or insect that attracts prey—and unfortunately, sometimes human curiosity. Their venom contains powerful neurotoxins that cause paralysis, potentially leading to respiratory failure within six hours if left untreated. What makes Death Adders particularly dangerous is their lightning-fast strike—among the quickest in the snake world at 0.15 seconds—giving victims virtually no time to react once they’ve approached too closely. Found throughout Australia, Papua New Guinea, and parts of Indonesia, these stocky, viper-like elapids (related to cobras despite their appearance) have historically been responsible for many fatalities, though deaths have declined significantly since antivenom became widely available.

Fer-de-Lance: The Americas’ Most Feared Serpent

The Fer-de-Lance (Bothrops asper) reigns as one of the Western Hemisphere’s deadliest snakes, responsible for more human fatalities in Central and South America than any other reptile. These pit vipers grow to impressive sizes, with females sometimes exceeding 2 meters (6 feet) in length, and possess remarkably long fangs that can deliver large quantities of hemotoxic venom deep into their victims. When a Fer-de-Lance strikes, its venom causes massive tissue destruction, internal bleeding, and potentially lethal cardiovascular shock, with untreated mortality rates reaching 30%. Their common name, which translates to “spearhead” in French, aptly describes their triangular head shape, while their excellent camouflage makes them nearly invisible against forest floors. What makes these snakes particularly dangerous is their combination of irritable temperament, tendency to freeze rather than flee when encountered, and habit of inhabiting agricultural areas and coffee plantations where barefoot workers frequently suffer bites—a public health crisis in many rural Central American communities where medical care may be hours away.

Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake: North America’s Heavyweight Champion

The Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake (Crotalus adamanteus) holds the title of North America’s largest and most dangerous venomous snake, capable of delivering more venom in a single bite than any other rattlesnake species. These imposing pit vipers can exceed seven feet in length and weigh over 30 pounds, with fangs measuring up to an inch long that can penetrate deep into tissue, delivering venom that contains a complex mixture of hemotoxins and cytotoxins. When an Eastern Diamondback bites, the venom rapidly begins destroying tissue, preventing blood clotting, and causing systemic effects that can lead to organ failure if not promptly treated. Though they possess the famous rattling warning system, these snakes will strike silently if suddenly startled or cornered, making them particularly dangerous during encounters in their native southeastern United States habitats. Despite their fearsome reputation, fatalities have become increasingly rare due to widely available antivenom and the snake’s declining population due to habitat loss and persecution—a reminder that many of these deadly species now face greater threats from humans than we do from them.

Staying Safe in Snake Territory

When traveling or living in regions inhabited by venomous snakes, several practical precautions can dramatically reduce your risk of dangerous encounters. Always wear appropriate footwear—sturdy boots that cover the ankles are ideal—and long pants when hiking or working in snake habitats, as most bites occur on the lower extremities. Remain vigilant by scanning the path ahead, avoiding reaching blindly into rock crevices, woodpiles, or dense vegetation where snakes may be sheltering. At night, always use a flashlight when walking in snake territory, as many deadly species are nocturnal hunters. If you encounter a snake, give it a wide berth—most bites occur when people attempt to kill, handle, or harass these animals. Learn to identify the venomous species in your region, but understand that even experts can misidentify snakes under field conditions. Finally, if a bite occurs, remember the modern first aid approach: keep the victim calm, immobilize the affected limb at heart level, remove constrictive items like rings or watches, and transport to medical care immediately—avoiding outdated and dangerous practices like cutting, sucking, or applying tourniquets.

Conclusion

The world’s deadliest snakes represent nature’s perfect balance of beauty, efficiency, and danger. While these serpents deserve our respect and even admiration for their evolutionary adaptations, they also warrant our caution. It’s worth noting that most venomous snakes avoid human contact when possible, biting only when threatened or cornered. The development of effective antivenoms has dramatically reduced fatalities from even the most toxic species. As we expand into previously wild habitats, human-snake encounters increase, making education about these creatures increasingly important. By understanding these magnificent predators rather than simply fearing them, we can better protect both ourselves and these essential