The world’s oceans, comprising over 70% of our planet’s surface, harbor some of nature’s most remarkable predators. Among these aquatic hunters, certain reptiles have evolved impressive adaptations that allow them not only to survive but to dominate in the open sea. These ancient creatures represent a fascinating evolutionary story—reptiles that returned to the water after their ancestors had conquered land. Unlike most reptiles that remain close to shorelines, these specialized hunters can navigate vast oceanic expanses, using deadly hunting techniques perfected over millions of years. From venomous sea snakes to massive marine lizards, these reptiles combine speed, stealth, and sometimes potent toxins to become some of the most feared predators in their domains.

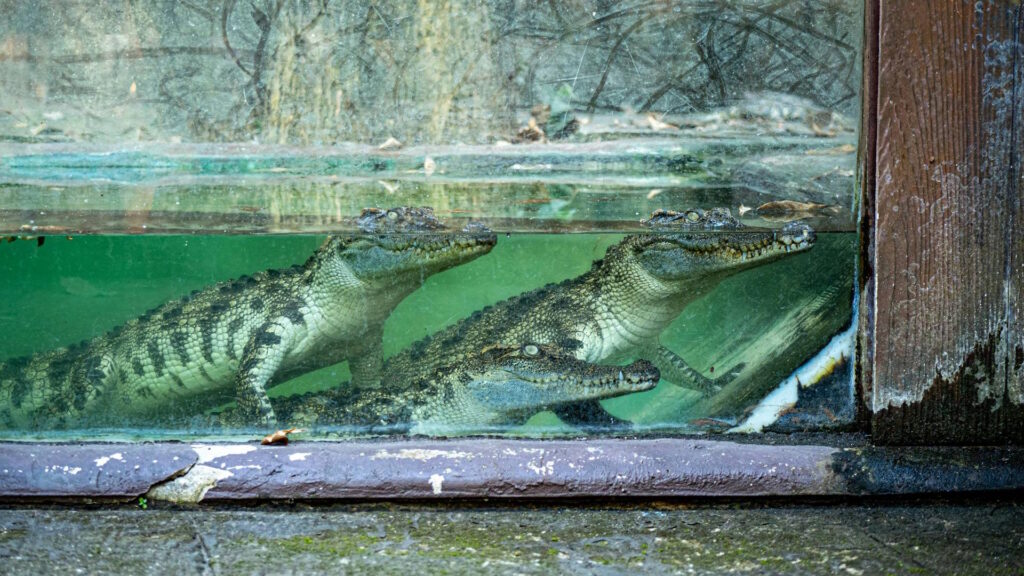

The Saltwater Crocodile: King of Coastal Waters

The saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus) earns its reputation as the world’s largest reptile and one of the most formidable ocean-going predators. Growing to lengths exceeding 20 feet and weighing up to 2,000 pounds, these massive reptiles possess extraordinary swimming abilities that allow them to traverse open ocean distances of over 900 kilometers. Their powerful tails propel them through water with surprising speed, while their elevated eyes and nostrils permit them to remain nearly invisible while stalking prey. Saltwater crocodiles have been documented making journeys between islands in the South Pacific, utilizing ocean currents to conserve energy during these marathon swims. Their bite force—measured at over 3,700 pounds per square inch—remains unmatched among all living animals, making even a brief encounter potentially fatal for humans or any other unfortunate creature crossing their path.

Yellow-Bellied Sea Snake: Perfectly Adapted Ocean Traveler

The yellow-bellied sea snake (Hydrophis platurus) stands as one of the most widely distributed reptiles on Earth, capable of traversing entire ocean basins. Unlike many sea snakes that remain near coral reefs, this species lives its entire life cycle in the open ocean, from birth to death without ever touching land. Its distinctive coloration—black above and bright yellow below—serves as perfect camouflage when viewed from above or below the water’s surface.

The yellow-bellied sea snake possesses a flattened, paddle-like tail that propels it efficiently through ocean swells, while specialized salt glands allow it to drink seawater by filtering out excess salt. Perhaps most terrifying is its venom potency—a single drop contains enough neurotoxins to kill several adult humans, attacking the nervous system and causing paralysis, respiratory failure, and death if untreated.

Olive Sea Snake: The Curious Hunter

The olive sea snake (Aipysurus laevis) has earned a reputation among divers for its unnervingly bold and curious nature in tropical Indo-Pacific waters. Growing up to 6.5 feet long, these powerful hunters often approach divers with apparent curiosity, which creates dangerous situations as their venom ranks among the most potent of all sea snakes. Their specialized tail muscles allow them to change direction instantly, darting through coral reefs with exceptional agility while hunting fish, eels, and crustaceans.

Olive sea snakes can remain submerged for up to two hours, diving to depths exceeding 70 meters during hunting forays. Unlike many reptiles, they give birth to live young in the ocean, with each baby snake already equipped with fully functional venom glands—making even juvenile encounters potentially deadly to humans.

Beaked Sea Snake: The Silent Killer

The beaked sea snake (Hydrophis schistosus), sometimes called the hook-nosed sea snake, carries the grim distinction of causing more human fatalities than any other sea snake species. Found primarily in the waters of Southeast Asia, the Persian Gulf, and northern Australia, this relatively small sea snake—rarely exceeding 4 feet—possesses venom estimated to be 8 times more potent than that of a cobra. The beaked sea snake has adapted to hunt in murky estuaries and silty ocean waters where visibility is poor, using specialized sensory organs to detect the electrical fields generated by hiding prey.

Their venom contains powerful myotoxins that rapidly break down muscle tissue, potentially leading to kidney failure even with medical intervention. Commercial fishermen are particularly vulnerable to bites when these aggressive snakes become entangled in fishing nets, accounting for numerous deaths annually across their range.

Marine Iguana: The Ocean Vegetarian

The marine iguana (Amblyrhynchus cristatus) of the Galápagos Islands stands as the world’s only oceangoing lizard, representing a fascinating evolutionary adaptation. Unlike the predatory reptiles on this list, these remarkable lizards dive into the Pacific Ocean to graze on underwater algae and seaweed, sometimes descending to depths of 30 feet or more. Their powerful tails and specialized claws allow them to maneuver through strong ocean currents while clinging to rocks in the surf zone.

Marine iguanas have evolved specialized glands that “sneeze” out excess salt consumed during their underwater feeding sessions, often leaving their heads crusted with white salt deposits. Though not dangerous to humans, these unique reptiles face their own challenges, including the fact that their body temperature can drop nearly 10°C during extended feeding dives, requiring them to bask extensively to rewarm after ocean forays.

Leatherback Sea Turtle: The Ocean Wanderer

The leatherback sea turtle (Dermochelys coriacea) stands as the largest of all living turtles and the fourth-heaviest modern reptile, with adults regularly exceeding 1,500 pounds. Unlike other sea turtles, leatherbacks have abandoned the hard shell, instead evolving a leather-like carapace consisting of small bones embedded in tough, oily connective tissue that allows them to dive deeper than any other reptile—recorded at depths exceeding 4,000 feet. These remarkable swimmers undertake the longest migrations of any sea turtle, crossing entire ocean basins between feeding and nesting grounds, with some individuals traveling over 10,000 miles annually.

While not venomous or aggressive toward humans, leatherbacks possess powerful jaws specialized for crushing their primary prey—jellyfish—and could deliver a significant defensive bite if threatened or mishandled. Their ability to maintain body temperatures up to 18°F warmer than surrounding water allows them to venture into near-freezing seas where no other reptiles can survive.

Black-Banded Sea Krait: The Amphibious Assassin

The black-banded sea krait (Laticauda semifasciata) represents one of the ocean’s most perfectly designed predators, combining exceptional swimming abilities with a terrestrial lifestyle. Unlike fully marine sea snakes, these striking black-and-blue banded reptiles must return to land to digest their prey, mate, and lay eggs, making them true amphibious hunters. Their venom ranks among the most potent of all snakes—containing powerful neurotoxins that can cause paralysis and death within hours—yet they rarely bite humans unless severely provoked.

Black-banded sea kraits can hold their breath for impressive periods, typically hunting underwater for 30-45 minutes while probing crevices in coral reefs for hiding fish and eels. Their specialized paddle-shaped tail provides excellent propulsion through ocean waters, while their valvular nostrils and ability to seal their mouths using specialized scales allow for extended submarine hunting expeditions.

Stokes’ Sea Snake: The Deep-Water Specialist

The Stokes’ sea snake (Astrotia stokesii) has earned its reputation as one of the largest and most venomous sea snakes in the world, regularly growing to lengths exceeding 6 feet. Unlike many sea snakes that hunt in shallow coastal waters, this species specializes in deeper offshore habitats, sometimes found more than 50 miles from the nearest land. Their bodies feature a dramatic bulky, almost barrel-shaped design that tapers to a highly compressed paddle-like tail, providing remarkable swimming power in open ocean environments. The Stokes’ sea snake possesses enormous venom glands that extend nearly 20% of their body length, producing a potent neurotoxic venom that can cause respiratory paralysis within hours. Though rarely encountered by humans due to their offshore preferences, fishermen occasionally pull these powerful snakes up in deep-water trawl nets, creating extremely dangerous handling situations.

Pelagic Sea Snake: The True Ocean Drifter

The pelagic sea snake (Hydrophis pelagicus) represents one of the few sea snake species truly adapted for permanent life in the open ocean, never needing to approach coastlines throughout its life cycle. These specialized hunters have evolved to follow ocean convergence zones—areas where currents meet and concentrate marine life—drifting with these productive water masses across vast distances. Their distinctive body shape features an exceptionally thin neck that rapidly widens toward the tail, creating a silhouette that confuses potential predators approaching from below.

Pelagic sea snakes possess specialized sensory organs that can detect minute pressure changes in the water, allowing them to locate schools of fish even in darkness or murky conditions. Their venom, while less studied than coastal species, contains powerful neurotoxins that can immobilize fish almost instantly, enabling these relatively small snakes to subdue prey many times their size in the challenging open ocean environment.

Banded Sea Krait: The Reef Hunter

The banded sea krait (Laticauda colubrina) combines beautiful coloration with deadly efficiency, featuring distinctive black and blue-gray bands that wrap around its body. Unlike fully aquatic sea snakes, these kraits maintain a dual lifestyle, hunting in ocean waters but returning to land to rest, digest, mate, and lay eggs on remote tropical islands and coastlines.

Their specialized venom is among the most potent of all snake toxins—estimated at 10 times stronger than a cobra’s—yet they possess a remarkably docile temperament, rarely biting humans even when handled. Banded sea kraits typically hunt by probing coral reef crevices and holes with their heads, using their forked tongues to “smell” hidden moray eels and small fish that constitute their preferred prey. Female kraits grow significantly larger than males, sometimes reaching lengths over 5 feet, allowing them to tackle larger prey items and dive to greater depths during hunting expeditions.

Komodo Dragon: The Swimming Monitor

While primarily terrestrial, the Komodo dragon (Varanus komodoensis)—the world’s largest lizard—has demonstrated remarkable swimming abilities that have allowed it to colonize multiple Indonesian islands separated by ocean channels. These massive reptiles, weighing up to 300 pounds, possess powerful legs that they can tuck against their bodies while using their muscular tails as propulsion, enabling them to swim distances exceeding 5 kilometers between islands. Komodo dragons occasionally hunt in shallow marine environments, taking advantage of their excellent sense of smell to locate dead fish, sea turtles, or other marine animals along shorelines. Their saliva harbors over 50 strains of bacteria along with mild venom components that prevent blood clotting, creating a deadly combination for any prey that escapes the initial attack but sustains even minor wounds. When swimming in ocean channels, even adult Komodo dragons remain vulnerable to large sharks and saltwater crocodiles—creating a rare situation where these apex predators become potential prey.

Belcher’s Sea Snake: The Most Venomous

The Belcher’s sea snake (Hydrophis belcheri) has earned a fearsome reputation as potentially possessing the most toxic venom of any snake in the world, with some studies suggesting its venom is 100 times more potent than that of an inland taipan. Fortunately for humans, this slender, yellow-and-green banded sea snake displays a remarkably docile temperament and rarely injects venom even when provoked, with a specialized narrow head that makes delivering a bite to humans difficult. Their exceptional swimming abilities allow them to hunt throughout the tropical western Pacific, using specialized lungs that extend nearly the entire body length to remain submerged for hours while hunting. The Belcher’s sea snake possesses remarkable adaptations for marine life, including specialized scales that trap an air bubble against the skin, helping with buoyancy control and possibly serving as a secondary respiratory surface during extended dives. Recent research suggests these snakes may be able to detect changes in water pressure that precede storms or tsunamis, allowing them to seek deeper water before dangerous conditions develop.

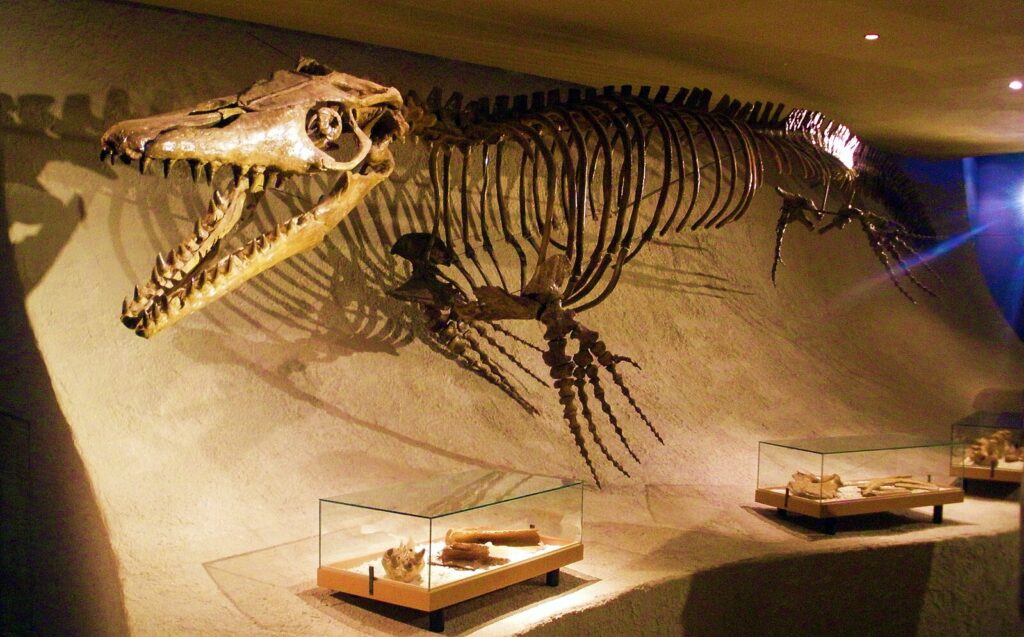

The Ancient Sea Monsters: Extinct Marine Reptiles

While today’s ocean-going reptiles are impressive, they pale in comparison to the marine reptiles that dominated prehistoric seas. The Mesozoic Era witnessed the evolution of truly gigantic marine reptiles including mosasaurs—massive predatory lizards reaching lengths of 50 feet that ruled the oceans during the late Cretaceous period. Ichthyosaurs evolved dolphin-like bodies with some species exceeding 70 feet in length, while long-necked plesiosaurs inspired modern sea serpent legends with their unusual body proportions.

These extinct marine reptiles developed adaptations far beyond modern species, including specialized fins, streamlined bodies, and in some cases live birth in open ocean environments. Fossil evidence suggests mosasaurs possessed particularly deadly hunting adaptations, including a flexible jaw similar to modern snakes that allowed them to consume enormous prey items. The reign of these magnificent marine reptiles ended with the K-T extinction event approximately 66 million years ago, leaving ecological niches that would eventually be filled by modern marine mammals and the surviving reptilian lineages that venture into today’s oceans.

Conclusion

The reptiles that have mastered open ocean environments represent extraordinary evolutionary success stories. From the lethal venom of sea snakes to the massive jaws of saltwater crocodiles, these animals have developed specialized adaptations that allow them to thrive in one of Earth’s most challenging habitats. While encounters with humans remain relatively rare due to the vastness of ocean environments, these creatures deserve both our respect and conservation efforts. Many face mounting threats from habitat destruction, climate change, and direct human exploitation.

Understanding the remarkable abilities of these ocean-going reptiles provides not only fascinating biological insights but also underscores the importance of preserving marine ecosystems for future generations. These ancient lineages, having survived multiple mass extinctions, now face perhaps their greatest challenge in coexisting with human civilization across the world’s interconnected oceans.