The fascinating world of snakes includes many remarkable survival adaptations, and perhaps one of the most impressive is their ability to go extended periods without food. Unlike mammals that require regular meals, snakes have evolved metabolic systems that allow them to survive what humans would consider extreme fasting. Whether you’re a snake owner concerned about your pet’s appetite, a wildlife enthusiast, or simply curious about these remarkable reptiles, understanding the feeding patterns and fasting capabilities of non-venomous snakes reveals much about their evolutionary success and physiological marvels. This article explores the surprising feeding habits of non-venomous snakes and the various factors that influence how long they can survive without a meal.

The Remarkable Metabolism of Snakes

Snakes possess one of the most efficient metabolic systems in the animal kingdom, specifically adapted for their predatory lifestyle. Unlike mammals who burn energy constantly, snakes can dramatically lower their metabolic rate during periods between meals, sometimes by up to 70%. This remarkable adaptation allows them to conserve energy when food is scarce or during brumation (the reptilian equivalent of hibernation). Their cold-blooded nature means they don’t expend energy maintaining body temperature, further reducing their caloric needs. This specialized metabolism is the primary reason snakes can survive fasting periods that would be fatal to most other vertebrates.

Species Variations in Fasting Capability

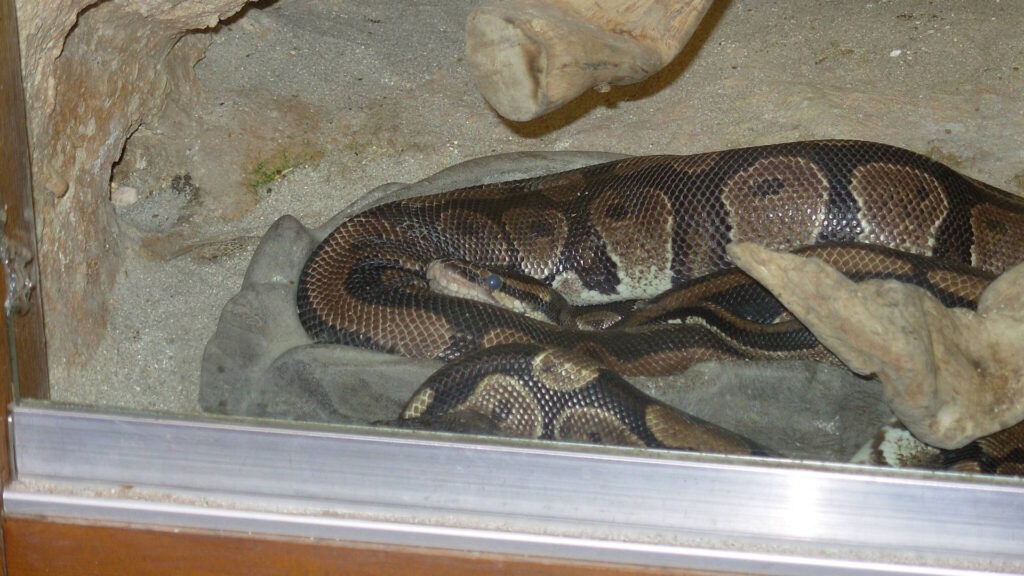

The duration a non-venomous snake can go without eating varies dramatically depending on the species. Larger constrictors like pythons and boas can survive the longest without food, with adult specimens potentially going 6-12 months or even longer without eating when necessary. Medium-sized colubrids such as rat snakes and king snakes typically manage 2-3 months without food while maintaining good health. Smaller species like garter snakes and ribbon snakes have higher metabolic rates relative to their size and generally require more frequent feeding, typically going only 2-4 weeks between meals in the wild. These variations reflect evolutionary adaptations to different ecological niches and prey availability patterns in their native habitats.

Age and Size Factors

A snake’s age and size significantly impact its ability to endure fasting periods. Juvenile snakes have proportionally higher metabolic rates to support their rapid growth and typically can’t go as long without food as their adult counterparts. For example, while an adult ball python might comfortably fast for 6 months, a juvenile of the same species might start showing concerning weight loss after just 4-6 weeks without food. Neonates (newly hatched snakes) are especially vulnerable and generally need to eat more frequently, often weekly, to support critical early development. The larger a snake grows, the more fat reserves it can maintain, and the longer it can potentially survive without feeding.

The Impact of Environmental Temperature

Temperature plays a crucial role in determining how long a snake can survive without food due to its direct influence on metabolic rate. In cooler temperatures, a snake’s metabolism slows dramatically, reducing energy expenditure and extending potential fasting periods. This is why many species can go months without eating during winter brumation when temperatures drop and they become relatively inactive. Conversely, in warm conditions, metabolic rates increase, causing snakes to burn through energy reserves more quickly. For snake owners, this means that maintaining appropriate temperature gradients in captivity can help regulate a snake’s feeding needs and energy consumption, particularly important during intentional fasting periods like breeding season.

Seasonal Fasting Patterns

Many non-venomous snakes naturally experience seasonal fasting as part of their annual cycle, particularly in temperate climates. During winter brumation, snakes may naturally refuse food for 3-5 months while their bodies function at minimal levels. Even tropical species that don’t truly brumate often experience reduced appetite during cooler or drier seasons. Some female snakes also fast during reproductive periods, particularly in the late stages of pregnancy or after egg-laying when they’re recovering. Male snakes of many species may refuse food during breeding season when finding mates takes priority over feeding. These natural fasting periods are physiologically normal and represent evolved adaptations to environmental rhythms.

Health Considerations During Fasting

While snakes can survive extended periods without food, distinguishing between normal fasting and problematic hunger strikes is crucial for their health. A healthy fasting snake should maintain muscle tone, responsiveness, and overall body condition despite not eating. Weight loss during fasting should be gradual rather than precipitous, with most healthy adult snakes losing only 10-15% of their body weight during normal fasting periods. Signs that fasting has become problematic include significant muscle wasting, sunken eyes, loose skin, and lethargy. Respiratory infections, mouth rot, or parasitic loads can complicate a snake’s ability to endure fasting periods, making regular health monitoring essential during extended non-feeding periods.

Record-Breaking Fasts in Captivity

Some documented cases of non-venomous snakes surviving extended fasts in captivity border on the incredible. Perhaps the most famous case involves a female ball python at the Adelaide Zoo that reportedly refused food for 23 months yet maintained good health throughout. Large constrictors like reticulated pythons and anacondas have been documented going 18-24 months without eating when in good body condition prior to the fast. A Burmese python at a wildlife sanctuary in Florida reportedly survived a 30-month fast, though it did lose substantial weight during this period. These extreme examples typically involve adult specimens with substantial fat reserves and are not representative of what should be expected or encouraged in typical captive situations.

Wild Versus Captive Fasting Abilities

Interesting disparities exist between the fasting capabilities of wild snakes versus their captive counterparts. Wild snakes typically develop more efficient fat storage capabilities and often have more robust metabolic adaptations for food scarcity due to natural selection pressures. In contrast, captive-bred snakes that have experienced consistent feeding throughout their lives may not develop the same physiological resilience to fasting. Snakes in the wild may be forced to endure longer fasts due to prey scarcity, seasonal changes, or environmental stressors, whereas captive specimens usually have more regular feeding opportunities. However, the stress and energy expenditure of hunting in the wild means captive snakes in controlled environments can sometimes safely fast longer than their wild counterparts who must remain active.

Preparing for Extended Fasting Periods

For snake owners anticipating natural periods when their pet might refuse food, preparation is key to ensuring the snake’s health. Ensuring the snake has reached optimal body condition before a predicted fasting period, such as brumation or breeding season, provides essential fat reserves to sustain them. A pre-brumation health check by a reptile veterinarian can identify any underlying issues that might complicate fasting. Proper hydration remains crucial even during fasting periods, as dehydration can quickly become life-threatening. Gradual temperature reduction for seasonal brumation should be implemented carefully, typically dropping no more than a few degrees per week to allow the snake’s metabolism to adjust naturally. These preparations can help ensure that natural fasting periods remain physiologically appropriate rather than becoming health emergencies.

Warning Signs of Problematic Fasting

While fasting is natural for snakes, owners should remain vigilant for signs that a non-feeding period has become problematic. Dramatic weight loss exceeding 15-20% of body weight indicates the fast is becoming dangerous, particularly if the weight loss occurs rapidly. Behavioral changes such as unusual lethargy, lack of muscle tone, or disinterest in normal activities may signal that fasting has progressed beyond healthy limits. Physical symptoms including sunken eyes, visible spine ridges, loose skin, or difficulty shedding suggest the snake is struggling nutritionally. Unusual posturing, difficulty moving, or trembling might indicate blood glucose issues related to extended fasting. If any of these warning signs appear, prompt veterinary attention is necessary, as force-feeding or supportive care may be required.

Feeding After a Fast: The Importance of Proper Reintroduction

Reintroducing food after an extended fast requires careful consideration to prevent complications like regurgitation or digestive stress. After long fasting periods, a snake’s digestive system essentially “shuts down” and needs time to reactivate properly. The first meal after an extended fast should be smaller than normal, typically about 50-60% of the snake’s regular prey size, to avoid overwhelming the digestive system. Ensuring proper temperatures during feeding is crucial, as the snake needs adequate heat to digest properly. Many experienced keepers wait until a snake has shown clear interest in food before offering it, recognizing that forced feeding after natural fasting can cause stress and potential health complications. With particularly long fasts, several smaller meals spaced over weeks may be necessary before returning to normal feeding schedules.

Myths and Misconceptions About Snake Fasting

Several prevalent myths about snake fasting persist in both the pet keeping community and general public. One common misconception is that all snakes can or should go months without eating, when in reality fasting capabilities vary dramatically between species, ages, and individual health status. Another myth suggests that a refusing snake is simply “not hungry” when refusal to feed might actually indicate illness, improper husbandry, or stress. Some owners mistakenly believe that snakes will eat when they’re hungry enough, but many snakes will starve rather than eat in stressful conditions or when ill. Perhaps most dangerously, some believe that fasting is always natural and never problematic, when in fact distinguishing between natural fasting and problematic hunger strikes requires careful monitoring and sometimes veterinary intervention.

Conclusion

The ability of non-venomous snakes to survive extended periods without food represents one of the most remarkable adaptations in the reptile world. From the impressive year-long fasts of large pythons to the more modest few weeks that small colubrids can manage, these capabilities have evolved as survival strategies in environments where prey availability fluctuates. For snake owners and enthusiasts, understanding the nuances of natural fasting—including how species, age, temperature, and health status affect fasting tolerance—provides crucial knowledge for proper care. While we might marvel at snakes’ ability to endure what seems like impossibly long periods without nourishment, it’s equally important to recognize when fasting transitions from a natural behavior to a health concern. With proper knowledge and monitoring, we can better appreciate this fascinating aspect of snake physiology while ensuring the wellbeing of both wild and captive specimens.