In a world where biodiversity loss continues at an alarming rate, conservation success stories shine like beacons of hope. Among these triumphs are remarkable tales of reptile species that have faced extinction and returned from the edge of oblivion. These cold-blooded survivors have overcome habitat destruction, hunting, invasive species, and climate change through dedicated conservation efforts. Their stories not only demonstrate the resilience of nature but also humanity’s capacity to reverse ecological damage when committed to preservation. From massive crocodilians to tiny island lizards, these reptilian comebacks remind us that with proper protection, scientific research, and community involvement, we can restore what once seemed lost forever.

The American Alligator: A Conservation Icon

Perhaps the most celebrated reptilian recovery story belongs to the American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis), which once teetered on extinction’s edge due to unregulated hunting and habitat loss. By the 1960s, these prehistoric-looking creatures had vanished from many areas of their historic range across the southeastern United States. The landmark Endangered Species Preservation Act of 1966 (a precursor to the Endangered Species Act) provided critical protection, halting the commercial hunting that had decimated populations. Following decades of strict protection, habitat preservation, and captive breeding programs, alligator populations rebounded so successfully that they were removed from the endangered species list in 1987. Today, with an estimated population exceeding one million individuals, the American alligator stands as a powerful testament to what conservation efforts can achieve when given proper support and time.

The Komodo Dragon’s Island Sanctuary

The world’s largest lizard, the Komodo dragon (Varanus komodoensis), faced a combination of threats that nearly spelled its demise on its native Indonesian islands. Habitat encroachment, poaching, and declining prey populations pushed these formidable predators toward extinction in the mid-20th century. The establishment of Komodo National Park in 1980 created a protected sanctuary spanning several islands, giving these ancient reptiles the space and safety they desperately needed. The park’s creation, combined with anti-poaching efforts and sustainable tourism practices, helped Komodo dragon numbers recover substantially. Scientific research programs that monitor population health, breeding patterns, and genetic diversity have further strengthened conservation efforts. Though still classified as endangered by the IUCN, stable populations of approximately 3,000-4,000 dragons now inhabit their protected island homes, drawing responsible ecotourists who contribute to local conservation funding.

The Remarkable Recovery of the Nile Crocodile

The Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus), once hunted relentlessly for its valuable skin, experienced catastrophic population declines across much of Africa during the mid-20th century. By the 1940s and 1950s, unregulated hunting had decimated populations to the point where they disappeared entirely from some regions. International trade restrictions through CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species) in the 1970s marked a turning point in the species’ recovery. These protections, combined with sustainable ranching programs that reduced pressure on wild populations while providing economic incentives for conservation, allowed numbers to rebound dramatically. Today, while still facing localized threats, healthy Nile crocodile populations have been reestablished across much of their historic range, with estimated numbers in the hundreds of thousands. The species’ recovery demonstrates the effectiveness of combining legal protection with economic models that make conservation financially beneficial to local communities.

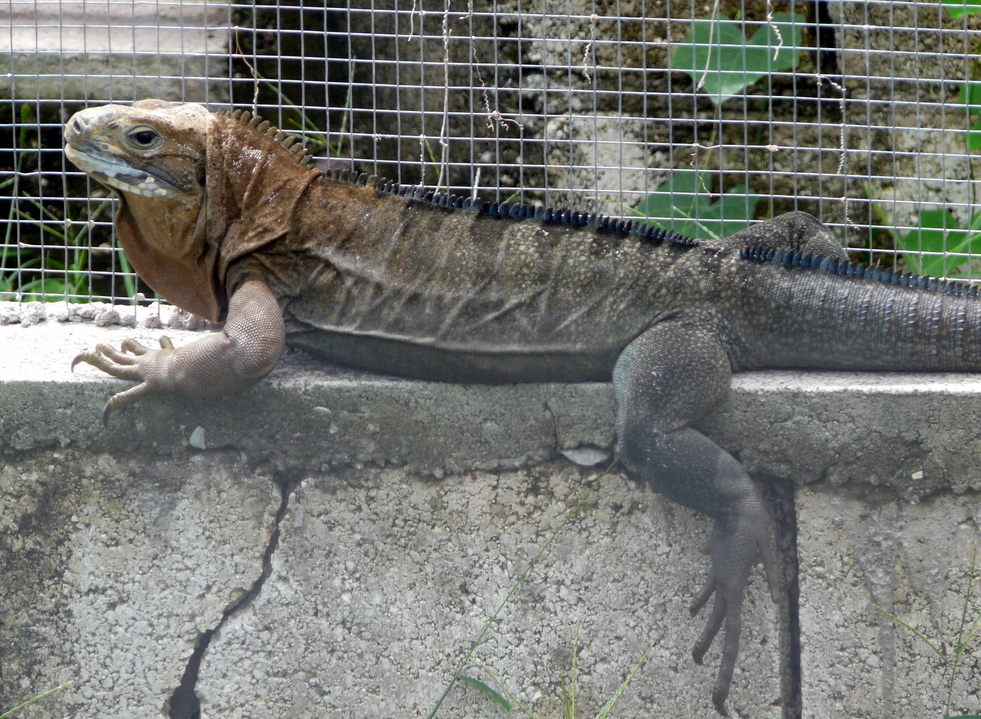

The Grand Cayman Blue Iguana’s Return

The Grand Cayman Blue Iguana (Cyclura lewisi) represents one of the most dramatic reptile recoveries in conservation history, having been pulled back from the absolute brink of extinction. In 2002, fewer than 25 of these striking blue lizards remained in the wild on Grand Cayman Island, victims of habitat destruction, feral predators, and vehicular deaths. The Blue Iguana Recovery Program, spearheaded by the National Trust for the Cayman Islands, implemented an intensive captive breeding program combined with habitat protection initiatives. Dedicated facilities were established to raise young iguanas until they reached a size that improved their survival chances against predators. Through methodical breeding, careful reintroduction, and the creation of protected reserves, the population has grown to over 1,000 individuals living in the wild today. The program highlights how focused efforts targeting a single species can achieve remarkable results, even when starting with a population on the verge of disappearing forever.

The Loggerhead Sea Turtle’s Coastal Comeback

Loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta) faced multiple threats that drove their numbers dangerously low worldwide, including beach development, fishing bycatch, light pollution disorienting hatchlings, and direct harvesting of eggs and adults. Conservation efforts beginning in the 1970s included the protection of nesting beaches, installation of turtle-excluder devices in fishing nets, and regulations on coastal lighting during nesting season. Community-based nest monitoring programs enlisted volunteers to protect nests and ensure hatchlings safely reached the sea. In the United States, particularly along the Florida coast, these combined approaches have yielded impressive results, with nesting numbers showing consistent increases over recent decades. Between 2000 and 2020, loggerhead nesting in Florida—which represents the largest nesting population in the western hemisphere—showed a substantial upward trend, with some years recording over 100,000 nests. While global challenges remain, the loggerhead’s recovery in certain regions demonstrates how coordinated conservation across various sectors can reverse declining populations.

The Gharial’s Fight Against River Degradation

The gharial (Gavialis gangeticus), with its distinctive narrow snout adapted for catching fish, once thrived in rivers across the Indian subcontinent but suffered catastrophic declines due to dam construction, water pollution, and fishing practices. By the 1970s, fewer than 200 individuals remained in the wild, placing them among the most endangered reptiles on Earth. Conservation initiatives included establishing protected sanctuaries along key river systems, developing captive breeding centers, and implementing “head-start” programs where hatchlings are raised in protected environments before release. India’s National Chambal Sanctuary became particularly important for gharial recovery, providing protected habitat along a 400-kilometer stretch of river. While still critically endangered, the global population has increased to approximately 650-700 mature individuals—a meaningful improvement, though still precarious. The gharial’s ongoing recovery highlights the complex challenges of conserving aquatic reptiles in river ecosystems affected by multiple human pressures, demonstrating that persistence and multifaceted approaches can yield results even in difficult circumstances.

The Antiguan Racer: Island Conservation Success

The Antiguan racer (Alsophis antiguae), a harmless snake native to the Caribbean, was driven to near-extinction by introduced mongoose predators and habitat degradation on Antigua. By 1995, only about 50 individuals survived on the tiny Great Bird Island, making it one of the world’s rarest snakes. The Antiguan Racer Conservation Project launched a comprehensive recovery strategy that included mongoose eradication from key offshore islands, habitat restoration, and carefully planned translocation of racers to mongoose-free islands. Educational outreach transformed local attitudes toward the snake from fear to pride in this unique national treasure. These multifaceted efforts produced remarkable results—the population has grown to approximately 1,000 individuals distributed across multiple islands. The Antiguan racer’s recovery demonstrates how removing invasive predators can allow native reptile populations to rebound rapidly and how changing public perception is often crucial to conservation success.

The Chinese Alligator’s Cultural Preservation

The Chinese alligator (Alligator sinensis), a smaller cousin of the American alligator, was driven to the brink of extinction by habitat loss in the Yangtze River basin and persecution based on unfounded fears. By the early 2000s, fewer than 150 individuals remained in the wild, primarily in Anhui Province. China established the Anhui Research Center of Chinese Alligator Reproduction, which developed successful breeding protocols that have produced thousands of alligators over decades. Reintroduction efforts have established new wild populations in protected wetland reserves, while community education programs have worked to shift cultural perceptions of the alligator from a nuisance to a valuable part of China’s natural heritage. Though still endangered with an estimated wild population of 200-300 individuals, the combination of captive breeding success and habitat protection has prevented what once seemed an inevitable extinction. The species’ recovery incorporates both modern conservation science and traditional Chinese values of harmony with nature, creating a culturally relevant conservation model.

The Jamaican Iguana’s Rediscovery and Rescue

The Jamaican iguana (Cyclura collei) represents one of conservation’s most inspiring rediscovery stories, having been presumed extinct until a hunting dog caught a live specimen in 1990. Prior to this unexpected discovery, the species had last been documented in the 1940s and was believed to have been eliminated by introduced mongoose predators and habitat destruction. The Jamaican Iguana Recovery Program quickly mobilized to save the remnant population of fewer than 50 individuals found in the remote Hellshire Hills. Conservation strategies included predator control, nest protection, headstarting of hatchlings, and habitat protection through the establishment of the Portland Bight Protected Area. A particularly successful component has been the head-starting program, where hatchlings are raised in safe facilities until large enough to better resist mongoose predation. More than 30 years of dedicated work has increased the wild population to approximately 400 individuals—still endangered but steadily growing. The Jamaican iguana’s recovery demonstrates the value of never giving up on “lost” species and how rapid intervention can save a species rediscovered on extinction’s edge.

The St. Croix Ground Lizard’s Island Translocation

The St. Croix ground lizard (Pholidoscelis polops) had been eliminated from most of its native range on St. Croix in the U.S. Virgin Islands by the 1960s, primarily due to predation by introduced small Indian mongooses. The colorful lizard survived only on two tiny mongoose-free offshore islands, Protestant Cay and Green Cay, with a combined area of less than 12 acres. Conservation biologists recognized that these small populations remained vulnerable to hurricanes, disease, or accidental mongoose introduction. In a strategic move to secure the species’ future, lizards were carefully translocated to establish new populations on Buck Island Reef National Monument after mongoose eradication was completed there in the early 2000s. This translocation succeeded beyond expectations, with the lizard population on Buck Island growing from 57 founders to thousands of individuals within a decade. By creating multiple, separate populations across different islands, conservationists dramatically reduced the species’ extinction risk while demonstrating the effectiveness of translocation as a conservation tool.

The Burmese Starred Tortoise’s Fight Against Wildlife Trafficking

The Burmese starred tortoise (Geochelone platynota), distinguished by the star-like patterns on its high-domed shell, was driven to functional extinction in the wild by the early 2000s due to relentless poaching for the international pet trade and Chinese medicine markets. With essentially no wild population remaining, the species’ survival depended entirely on captive assurance colonies maintained by the Turtle Survival Alliance and Myanmar’s wildlife authorities. A carefully managed captive breeding program produced thousands of tortoises, while simultaneously, protected areas were established and secured in the tortoise’s native dry forests of central Myanmar. Beginning in 2013, conservationists began methodically reintroducing captive-bred tortoises to these protected areas, with local communities employed as wildlife guardians to prevent poaching. By 2019, more than 1,000 tortoises had been released, with promising survival and reproduction rates documented in the wild. This recovery represents an extraordinary reversal from a species once considered ecologically extinct to one with multiple wild breeding populations, demonstrating that even species eliminated from nature can sometimes be restored.

The Western Swamp Tortoise: Australia’s Climate Adaptation Model

Australia’s western swamp tortoise (Pseudemydura umbrina) has the unfortunate distinction of being one of the world’s rarest reptiles, having declined to fewer than 50 individuals by the 1980s due to massive habitat loss near Perth, Western Australia. With 97% of its wetland habitat converted to agriculture and urban development, this small freshwater tortoise faced seemingly insurmountable odds. A recovery program initiated in the 1980s combined captive breeding at Perth Zoo with intense habitat management of the few remaining swamp fragments. As climate change began causing the species’ traditional habitats to dry out earlier each year, conservationists pioneered an innovative approach: assisted colonization to wetlands outside the tortoise’s historic range but projected to have suitable conditions in the future. This forward-thinking strategy, combined with captive breeding success that has produced over 800 tortoises for wild release, has increased the population to approximately 500 individuals in nature. The western swamp tortoise’s ongoing recovery serves as a model for how conservation must adapt to changing climate conditions to ensure long-term species survival.

Lessons From Reptile Conservation Success Stories

These remarkable reptilian recoveries share several key elements that provide valuable insights for broader conservation efforts. First, legal protection matters—in nearly every case, formal protection status created the foundation upon which recovery could begin. Second, habitat preservation and restoration proved essential, as even well-protected species cannot survive without suitable places to live. Third, addressing specific threats—whether invasive predators, poaching, or pollution—required targeted interventions based on scientific understanding of each species’ ecology. Fourth, captive breeding and head-starting programs provided crucial population boosts while wild habitats were secured and improved. Finally, community involvement transformed local people from potential threats to active partners in conservation, creating sustainable long-term guardians for these species. As biodiversity loss accelerates globally, these success stories remind us that extinction is not inevitable when human determination, scientific knowledge, and adequate resources combine to protect Earth’s remarkable reptilian diversity.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the recovery of these reptile species from the brink of extinction represents both a scientific achievement and a testament to human capacity for environmental stewardship. From massive alligators to tiny island lizards, each success story required years—often decades—of dedicated effort across multiple fronts. While many of these species remain vulnerable and require ongoing protection, their trajectories have fundamentally changed from decline toward stability or growth. As we face growing environmental challenges worldwide, these reptilian comebacks offer powerful evidence that conservation works when properly supported. They challenge the narrative of inevitable loss and demonstrate that even the most endangered species can recover when given a chance. These cold-blooded survivors, having weathered millions of years of evolution only to nearly disappear in our lifetime, now stand as living monuments to what we can save when we choose to act.