While today’s crocodiles and alligators strike fear in many hearts as apex predators of rivers and swamps, they are merely shadows of their prehistoric ancestors. The fossil record reveals crocodylomorphs—the group containing modern crocodilians and their extinct relatives—that were far more terrifying, diverse, and dominant than the species we know today. From ocean-going giants with flippers to galloping land predators and even herbivores, ancient crocodiles evolved into ecological niches we would never associate with modern crocodilians. Their reign across land, sea, and freshwater environments showcases one of evolution’s most remarkable success stories—and presents us with creatures that would make today’s crocodiles seem almost tame by comparison.

The Crocodile Family Tree: A 240-Million-Year Legacy

Modern crocodilians—crocodiles, alligators, gharials, and caimans—represent just a narrow branch of a once-sprawling evolutionary tree that dates back to the Triassic period, over 240 million years ago. The earliest crocodylomorphs emerged around the time dinosaurs first appeared, evolving from archosaurs, the group that also gave rise to dinosaurs and, eventually, birds. Unlike today’s semi-aquatic ambush predators, the earliest crocodile relatives were small, fully terrestrial animals that ran on long legs. This extended evolutionary history makes the crocodilian lineage one of the most enduring and successful vertebrate groups on Earth, surviving multiple mass extinctions that wiped out countless other species, including the non-avian dinosaurs. Their evolutionary success stems from remarkable adaptability, with hundreds of extinct species representing diverse body types and ecological roles that modern crocodilians no longer fill.

Deinosuchus: The “Terrible Crocodile” That Hunted Dinosaurs

Among the most nightmarish ancient crocodilians was Deinosuchus, aptly named the “terrible crocodile,” which prowled the coastal waters of North America during the Late Cretaceous period approximately 82 to 73 million years ago. This monster reached estimated lengths of up to 39 feet (12 meters) and weighed as much as 8.5 tons, with a skull alone measuring nearly 6 feet long. Fossil evidence suggests Deinosuchus had bite forces strong enough to crush turtle shells and attack even large dinosaurs, with dinosaur bones bearing distinctive Deinosuchus tooth marks confirming these terrifying encounters. Unlike modern crocodiles with relatively uniform teeth, Deinosuchus possessed specialized dentition including banana-sized teeth designed for crushing prey. Perhaps most chilling is that this massive predator likely employed ambush tactics similar to modern crocodiles but on a far more devastating scale, pulling dinosaurs into water as they came to drink—making it one of the few non-dinosaurian predators capable of preying on large dinosaurs.

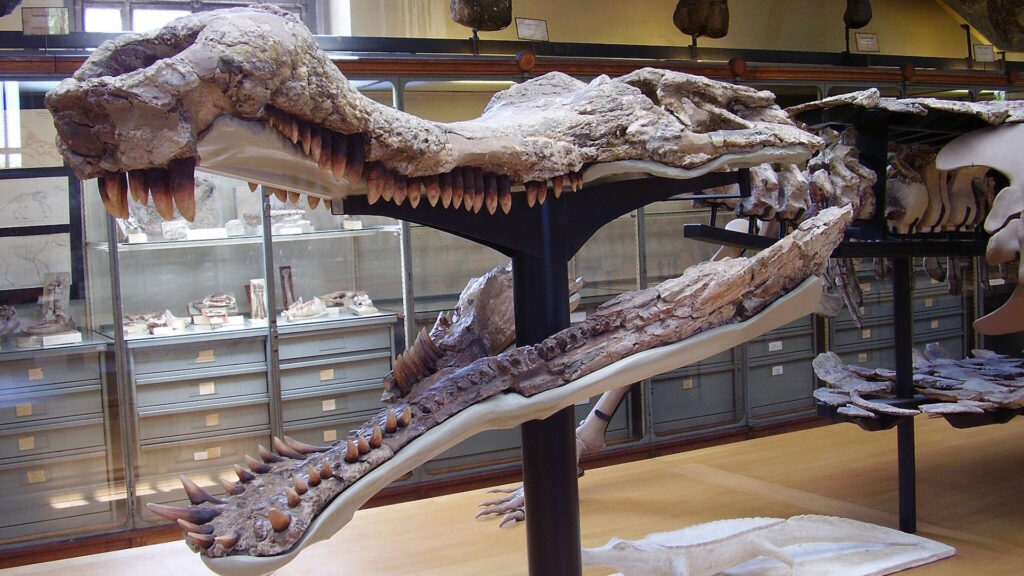

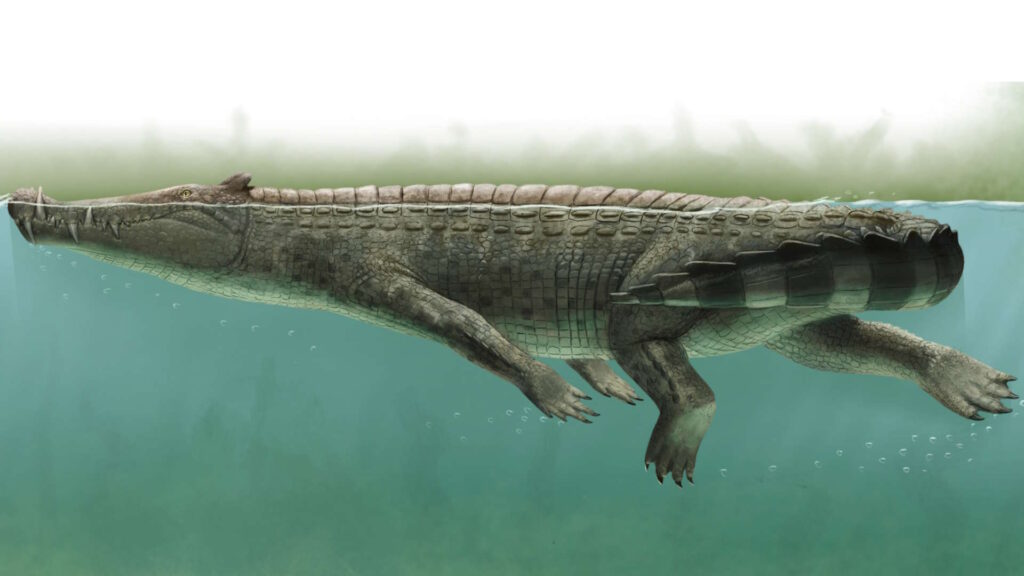

Sarcosuchus: The “Flesh Crocodile” That Dwarfed Modern Species

Sarcosuchus imperator, commonly called “SuperCroc,” terrorized river systems in what is now Africa and South America during the Early Cretaceous period approximately 112 million years ago. This colossus measured up to 40 feet (12 meters) long and weighed around 8 tons—roughly the weight of an adult African elephant. Unlike modern crocodiles, Sarcosuchus featured an expanded area at the end of its snout called a bulla, which may have allowed it to make distinctive calls or enhance its sense of smell. Its jaws contained over 100 teeth, each up to 6 inches long, designed for catching and holding struggling prey rather than cutting through flesh. Scientists believe Sarcosuchus continued growing throughout its life, potentially living for 50-60 years and reaching sizes far exceeding any modern crocodilian. Unlike today’s species that undergo relatively rapid growth followed by slowdown, Sarcosuchus maintained steady growth rates, allowing it to reach its enormous proportions.

Purussaurus: The Amazon’s Prehistoric Super-Predator

Between 8 and 5 million years ago during the Late Miocene, the wetlands of what would become the Amazon basin were dominated by Purussaurus brasiliensis, perhaps the largest caiman to ever exist. Conservative estimates place this behemoth at around 35 feet (10.5 meters) long, with skull measurements suggesting it could open its jaws more than 6 feet wide and generate bite forces exceeding 69,000 newtons—roughly ten times stronger than today’s saltwater crocodile. Purussaurus evolved in a unique ecosystem where South America was isolated as an island continent, allowing for the evolution of distinctive megafauna. Its massive size and power enabled it to prey upon giant prehistoric turtles, large mammals, and possibly even other crocodilians in its environment. Purussaurus represents the pinnacle of caiman evolution and stands as evidence that the ancient Amazon supported apex predators far more formidable than anything found there today, raising fascinating questions about how such massive predators affected ancient South American ecosystems.

Thalattosuchia: The Dolphin-Like Crocodiles That Conquered The Oceans

Perhaps the most dramatic departure from the crocodile body plan we recognize today came from the Thalattosuchia, a group of fully marine crocodylomorphs that evolved during the Early Jurassic period and thrived for nearly 75 million years. Unlike modern semi-aquatic crocodilians that maintain strong limbs for land movement, these “sea crocodiles” evolved flippers for steering, a streamlined body, and a powerful tail fluke for propulsion through open ocean environments. Their most extreme representatives, like Metriorhynchus, abandoned the heavy body armor typical of crocodilians in favor of a lighter, hydrodynamic build that closely resembled modern dolphins in both appearance and ecological niche. Some species developed specialized salt glands similar to those in marine turtles and sea snakes, allowing them to drink seawater and maintain salt balance while living permanently at sea. Thalattosuchians had vertically flattened tails for powerful swimming—unlike the laterally flattened tails of modern crocodiles—and some species evolved extreme specializations for hunting fast-moving prey like squid and fish in the open ocean.

Kaprosuchus: The “Boar Croc” With Saber Teeth

Discovered in Niger in 2009, Kaprosuchus saharicus has been nicknamed the “BoarCroc” due to its unusual dentition featuring three pairs of tusk-like teeth that protruded from its jaws when closed, similar to a boar’s tusks. This 20-foot-long terrestrial predator roamed North Africa approximately 95 million years ago during the Late Cretaceous period, bearing little resemblance to the modern crocodilians we know today. Kaprosuchus possessed long, muscular limbs positioned directly under its body rather than splayed to the sides, indicating it was capable of galloping at high speeds across land to actively pursue prey. Its eyes faced more laterally than the upward-facing eyes of modern crocodiles, further supporting the theory that it was primarily terrestrial rather than aquatic. Perhaps most striking were its specialized teeth and reinforced skull, suggesting Kaprosuchus was an active hunter that used its tusks to dispatch prey through powerful, slashing bites—a hunting strategy more reminiscent of big cats than modern crocodiles.

Quinkana: Australia’s Terrestrial Crocodile Terror

As recently as 40,000 years ago, Australia was home to Quinkana, a genus of terrestrial crocodiles that were among the continent’s top predators during the Pleistocene epoch. Unlike today’s Australian saltwater crocodiles that hunt in water, Quinkana species were fully terrestrial hunters with long legs adapted for running down prey across Australia’s ancient landscapes. Most distinctive were their blade-like, serrated teeth—more similar to those of carnivorous dinosaurs than modern crocodilians—specialized for slicing through flesh rather than gripping prey for drowning. Growing up to 23 feet (7 meters) in length, these “land crocodiles” would have been formidable hunters, potentially competing with marsupial predators like the marsupial lion (Thylacoleo) for prey. Quinkana’s extinction roughly coincides with human arrival in Australia, raising questions about whether early human hunters played a role in their disappearance. This recent extinction means Quinkana was among the last of the specialized terrestrial crocodilians, representing the final chapter of the group’s dominance on land.

Boverisuchus: The “Hoofed Crocodile” That Galloped Like A Horse

During the Eocene epoch approximately 50 million years ago, forests in what is now Germany and North America were stalked by Boverisuchus, a bizarre crocodylomorph that bore little resemblance to its semi-aquatic relatives. Nicknamed the “hoofed crocodile,” Boverisuchus had evolved specialized, compact foot bones that resembled primitive hooves, allowing it to run efficiently across hard ground. Unlike modern crocodilians that typically move with a sprawling gait, Boverisuchus held its legs directly under its body in a manner similar to mammals, enabling it to gallop at speeds that would have rivaled modern wolves. Its tall, narrow skull contained blade-like teeth specialized for slicing rather than gripping, indicating it was an active predator that chased down prey rather than ambushing it from water. Most remarkably, Boverisuchus represents a highly successful evolutionary experiment—a crocodilian lineage that essentially evolved to fill the ecological niche of large mammalian predators, competing directly with early carnivorous mammals in the warming world following the dinosaur extinction.

Simosuchus: The Vegetarian Crocodile With A Pug-Like Face

Not all ancient crocodylomorphs were fearsome predators—some evolved to fill completely unexpected ecological niches, as demonstrated by Simosuchus clarki from Madagascar. This bizarre crocodile relative from the Late Cretaceous period (around 70 million years ago) bore almost no resemblance to modern crocodilians, with a short, blunt snout reminiscent of a pug dog’s face and leaf-shaped teeth clearly adapted for processing plant material rather than tearing flesh. At just 2-3 feet (60-90 cm) long, Simosuchus was tiny compared to most crocodilians and possessed a short, stocky body covered in bony armor arranged in rectangular plates that formed a protective shell-like covering. Most surprising was its complete lack of aquatic adaptations—Simosuchus had short limbs positioned under its body for walking on land and likely never entered water by choice. The existence of herbivorous crocodylomorphs like Simosuchus demonstrates the remarkable evolutionary plasticity of the crocodile lineage, which experimented with dietary adaptations far beyond the carnivorous lifestyle we associate with crocodilians today.

Pristichampsus: The Crocodile That Walked Like A Big Cat

In the aftermath of the dinosaur extinction, an unusual group of crocodilians briefly dominated terrestrial predator niches across the Northern Hemisphere. Among them, Pristichampsus stood out as one of nature’s most unexpected evolutionary experiments—essentially a crocodile that evolved to fill the ecological role later dominated by big cats. Living approximately 56-45 million years ago during the Eocene epoch, Pristichampsus species reached lengths of 10 feet (3 meters) and moved on long, straight limbs that held their bodies well above the ground in a manner completely unlike modern crocodilians. Their serrated, ziphodont teeth resembled those of carnivorous dinosaurs or big cats—designed for slicing through flesh rather than gripping struggling prey. Most remarkably, fossil evidence suggests Pristichampsus had hoofed toes that would have allowed it to run efficiently across hard ground, possibly achieving speeds that would rival modern wolves. The existence of such specialized terrestrial predators among crocodilians demonstrates how dramatically different their evolutionary trajectory might have been had mammals not eventually dominated large predator niches.

Armadillosuchus: The Armored Crocodile That Dug For Prey

The Cretaceous period of Brazil produced one of the strangest crocodylomorphs ever discovered: Armadillosuchus arrudai, an animal that combined features of crocodiles and armadillos in a unique evolutionary package. This 6-foot-long (2-meter) predator possessed a body covered in articulated bony armor arranged in bands, similar to modern armadillos, which likely provided flexibility while maintaining protection from predators. Unlike typical crocodilians, Armadillosuchus had powerful, specialized forelimbs with enlarged claws clearly adapted for digging, suggesting it could burrow into the ground to either create dens or excavate prey. Its skull and teeth show a mixed dentition, with some teeth specialized for crushing hard materials—possibly the shells of ancient mollusks, crustaceans, or even eggs it might have unearthed. Armadillosuchus represents a specialized burrowing lifestyle unlike anything seen in modern crocodilians, demonstrating the remarkable adaptability of the crocodylomorph body plan to fill ecological niches we would never associate with crocodiles today.

Extinction Patterns: Why The Giants Disappeared

The disappearance of giant and specialized crocodylomorphs resulted from multiple extinction events and environmental changes across millions of years, rather than a single catastrophic event. During the end-Cretaceous mass extinction 66 million years ago, many specialized crocodylomorph lineages vanished alongside the non-avian dinosaurs, though the group as a whole survived better than many other reptiles due to their semi-aquatic lifestyle and ability to scavenge. Climate cooling during the Cenozoic era proved particularly challenging for crocodilians, which, being ectothermic (“cold-blooded”), saw their geographic range progressively restricted toward the equator as global temperatures declined. Competition with emerging mammalian predators after the dinosaur extinction placed additional pressure on terrestrial crocodylomorph species, gradually pushing surviving lineages toward the semi-aquatic ambush predator niche most occupy today. The most recent megafaunal crocodilian extinctions occurred during the Pleistocene and early Holocene periods, coinciding with human expansion across continents and suggesting our ancestors may have played a role in eliminating the last of the truly giant crocodiles from ecosystems where they had dominated for millions of years.

Evolutionary Lessons: What Ancient Crocodiles Teach Us About Adaptation

The remarkable diversity of ancient crocodylomorphs offers profound insights into evolutionary principles that extend far beyond this single group. Perhaps most striking is their demonstration of convergent evolution—the process by which unrelated organisms evolve similar traits in response to similar environmental pressures, as seen in marine crocodiles that independently evolved dolphin-like body plans. The crocodylomorph family tree also powerfully illustrates adaptive radiation, where a single lineage diversifies to fill multiple ecological niches, evidenced by crocodile relatives that variously became herbivores, diggers, ocean predators, and terrestrial hunters. Crocodylomorph evolution challenges our understanding of evolutionary constraints, showing how a basic body plan can be modified in unexpected ways over millions of years to produce forms that bear little resemblance to their ancestors. Most significantly, the restriction of crocodylomorphs from their former ecological diversity to the limited range and lifestyle of modern crocodilians serves as a sobering example of how climate change and competition can dramatically narrow evolutionary possibilities, confining once-diverse groups to specialized ecological corners from which they may never again emerge.

Conclusion

Modern crocodilians—intimidating as they may be—represent only a narrow slice of their group’s former diversity and prowess. The fossil record reveals crocodylomorphs that were larger, faster, more specialized, and occupied a far greater range of habitats and ecological niches than their living descendants. From the bus-sized Deinosuchus that preyed on dinosaurs to hoofed terrestrial hunters, dolphin-like ocean swimmers, and even plant-eaters, ancient crocodilians demonstrate evolutionary versatility that rivals any vertebrate group. Today’s crocodiles and alligators, impressive as they are, survive as conservative remnants of a once-dominant lineage—living fossils that hint at the remarkable adaptability an